When he agreed to send Oblates to Canada, in 1841, Bishop de Mazenod by and large foresaw the possibility of going out to evangelize the original natives of that country. Therefore it should not surprise us to see these missionaries rushing to help the Amerindian tribes as early as 1844. Hence, the sons of Bishop de Mazenod inherited the missions of Saguenay, Upper Saint-Maurice, Temiscamingue, Abitibi and, a few years later, the Western tribes.

The Quebec Amerindians

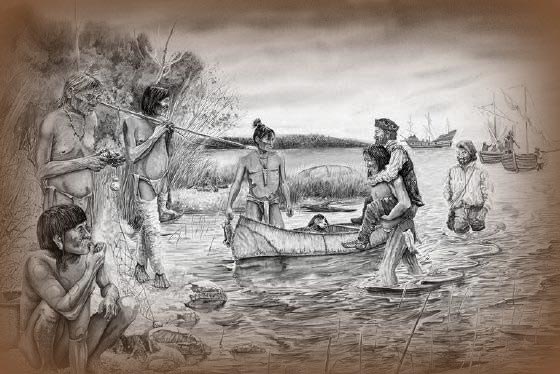

It is impossible to reminiscence on all of these valiant apostles who spared nothing to bring the Good News to the “children of the woodlands.” However, we can evoke the names of a few legendary individuals who constitute “a crown of unsung heroes.” The first ones who visited the Algonquians of Abitibi, as early as 1844, were Fathers Nicholas Laverdochère and Jean-Marie Nédélec. In order to reach Fort Albany, they had to make long trips by canoe on rivers, through dangerous rapids. Father Nédélec ran these risks twenty one times.

Among the Crees at James Bay, the best known Oblate was beyond doubt Father François-Xavier Fafard. He was called “Sapier” by the Amerindians who could not pronounce “Xavier” his usual first name. Father Damase Couture spent forty-five years of his life at Fort George, in the most complete isolation, where he was able to baptize only a few children. Bishops Henri Belleau and Jules Leguerrier, the first two bishops of the region, were able to multiply the missions thanks to the talents and dedication of many Oblate Brothers, such as Brothers Grégoire Lapointe and Charles Tremblay.

Among the Montagnais of the Saguenay, two names deserve our attention: Charles Arnaud and Louis Babel. The latter must be credited for having discovered the substrata of iron in the region that is today Schefferville. The Attikameks of the Upper Saint-Maurice and the Naskapis of Labrador, for their part, received visits from Fathers Médard Bourassa and Pierre Fiset. Father Maurice Ouimet spent himself for some fifty years among the Ojibways, west of James Bay. Even the Iroquois at Kahnawake learned the Good News thanks to Father Nicolas Burtin, who was their pastor for thirty-seven years, from 1855 to 1892.

In Western Canada

In 1846 the Western Amerindians in turn were drawn into the furrow of the Gospel. Dozens of nations, which rivaled in symbolic names, benefited from the dedication of Fathers Emile Grouard, Vital Grandin, Ovide Charlebois, and hundreds of other Oblates. We can name Father Albert Lacombe, with the Sauteux; Xavier Ducot, saved by a wolf, with the Peaux-de Lièvres; Jean Séguin, with the Loucheux, who waited three years for the delivery of windows for his house-chapel.

Difficulties and fruits of their first labors

All the missionaries of the first years had to withstand cold weather, hunger, and solitude.

In spite of their personal hardships, the Oblates brought numerous benefits to these Amerindian nations. Everywhere, they gave them books (dictionaries, etc.) written in their own language. As Father Joseph-Etienne Champagne, O.M.I. wrote: “What is outstanding in this missionary epic is not the number of conversions, but the fact that the Oblates are present in all the strategic points of a land as large as a continent.” And we could add: thanks especially to these unsung heroes who, like Saint Eugene de Mazenod, had “a Faith as large as the world.”

André DORVAL, OMI