Evangelizers being evangelized

Evangelizers being evangelized

Interview with Fr. Guillermo Siles, OMI

Recently, Fr. Guillermo Siles, OMI, passed through Rome. A formator of young religious, a former provincial superior, director of Radio Pio XII, among other tasks, and now, as a good communicator, he works in television programs. We took the occasion to interview him.

- As a Bolivian Oblate, you would know well the history and the beginnings of the Oblates in your country. Can you tell us something about that?

The Missionary Oblates arrived for the first time in Bolivia on 25 March 1925. They came from Germany and they were going to found a mission in the Bolivian Chaco; but in the war over the Chaco, Bolivia lost and the Chaco ended up in Paraguay. Therefore, the Oblates who had come to Bolivia ended up in Paraguay and they founded the Apostolic Vicariate of Pilcomayo.

On 18 July 1952, the Oblates arrived for a second time in Bolivia, but this time they were Canadians. They had been invited to dedicate themselves to evangelization.

At that time, Bolivia was passing through a very difficult situation. It was the year of the National Revolution. The peasants and the miners took power; they nationalized the mines and they carried out land reform. It was a very strong, popular movement that has affected our history to this day. The miners had been well trained in Cuba and in the Soviet Union and they were, logically, of communist tendency. Communism was growing in Bolivia.

The Canadian Oblates came into this environment.

- The Oblates had been invited by the Bolivian bishops. Why?

They were invited to fight communism and alcoholism. That was a serious problem because, in families, the miners consumed much alcohol; but what seemed most serious was communism.

From 1952 until 1963, it would be a great story, because at that stage the Oblates would come face to face with the social struggle; but for this they would have to face the miners, since it was now a state-controlled enterprise. They wanted to give new direction to the daily lives of the miners and they tried at first by focusing on the formation of young workers, and, inspired by the Young Catholic Workers, they founded the Catholic Workers League. To start the process of evangelization in families, they began the Christian Family Movement. This was the pastoral work of the missionaries at this stage.

- I believe that at first, they met strong resistance.

Indeed, for the implementation, they would have to endure the constant attack of the miners, especially the leaders who were very aggressively anticlerical; they said that the priests had come to take over, to get into the lives of the miners. So much so, that in the early years, they made the miners believe that the missionaries were CIA agents because they were “gringos” (Americans). Since they came from the North, they were regarded with suspicion: they would be able to spy on everything.

The truth is that, although they were not agents of the CIA, they had a clear objective: to bring about a very different lifestyle. Bolivia is a predominantly Catholic country and they wanted religion to continue strong.

As the years went by, the Oblates began to grasp the meaning of the Revolution, especially in the mining centers. It is here, among the miners, where they promoted family life, work, education. Later they opened a radio station, Radio Pio XII. Father Lino Grenier managed it and he used it to support evangelization. In this climate of confrontation from the beginning, the miners, who also had their own station, La Voz del Minero (The Voice of the Miner), hostility increased. So, if before, confrontation was in the street or in the chapel, now it leapt onto the airwaves. The miners’ leaders attacked the missionaries who responded by issuing messages of peace and tranquility, but in order that the Communists might not gain ground and might not impose their ideology.

- Can you give a concrete example of the air of hostility?

There is more than one. The antagonism was such that when an Oblate from Catavi, Father Enrique, hit a dog with his car, the union’s radio station broke the news as the editorial of the day: “Capitalist priest kills proletarian dog.” This story demonstrates the climate of confrontation.

Another anecdote: Fr. Mauricio Lefebvre, when he was pastor at Catavi, had to tackle the widespread problem of alcoholism. A woman selling chicha (a corn liquor) to the miners had a Santeria “santito” (image of a saint from the Santeria cult); he asked to borrow it. Her response: “I will lend it on one condition…if you buy some chicha.”

One day Father Mauricio learned that there was a party; he rushed to the scene and poured out their chicha. They almost lynched him, but because the priest was so tall, they could not manage it.

I repeat: the miners’ union wanted to impose a totalitarian regime. The Oblates confronted this and alcoholism; but they continued with the task of Christian formation.

- With the arrival of the Council, did anything change in this situation?

In pre-conciliar times, the Oblates had already moved toward Vatican II, speaking, preaching, and celebrating in the language of the people. The Oblates, along with other diocesan priests, wrote songs; they recorded an album with the Incan Mass, the whole Mass in Quechua. That is 60 years ago and it is still sung today, because it struck a chord with the people and because their songs are very popular.

But new winds were blowing in 1963 in the country. There was a new president, General Rene Barrientos (1919-1969). He was a dictator, but very popular. He was good-natured and he was organizing things. Moreover, the Oblates began to change their attitude toward the leaders of the mines. There was a new kind of relationship with the miners.

- Who changed: the miners or the Oblates?

Both. Fr. Gregorio Iriarte, a native of Navarre, Spain, entered the scene. He managed to connect with the political leaders, with the people and with the Church. Gradually the miners realized that the priests had not been against them, that there had been misunderstandings. Until then the miners had the slogan: “those damned shitty priests.” It was the expression they always used to point out priests, who were considered oppressors, because they opposed their lifestyle.

The year 1963 marks the beginning of the rapprochement and of normal relationships in everyday life. The Oblates came to Oruro to open a new mission among the mines and were surprised to come upon such a harsh and difficult reality. They wondered: Why are there no schools, health so bad, many children dying? How can we solve these circumstances of inhumane life? They opened missions in Oruro and Cochabamba to try to change the standard of living of the miners and peasants. They opened training centers for teachers: “We cannot allow people to remain illiterate.” They opened a Normal School, i.e., a teacher training school, and they began to prepare them. It was the first training initiative throughout the region.

- And now the anticommunist Oblates are the red priests…

That’s what the dictators began calling them. The Council opened and the Oblates felt compelled to fully live in relationship with the people. But in that conciliar period, the dictatorships returned to Bolivia. The priests generally sided with the people, because during the dictatorship, the soldiers went into towns, into mining centers and into the villages of farmers; they killed the leaders or took them prisoner or exiled them.

The Oblates, of course, sided with the people; they hid them and they defended their human rights, preventing exile or confinement. This was how the people saw the Oblates.

In 1967 the famous “Slaughter of San Juan” took place in Catavi. Radio Pius XII cried out to heaven, making it known throughout the country. The station had a starring role in reporting that and since then, it stood very much in solidarity with the people. From that time Radio Pío XII was very much scrutinized and the Oblates would be considered “red priests”.

- Later, Che would arrive and the option for the poor…

Yes, in Latin America, following the Council, we started to think about the option for the poor, the struggle for the poor. We had to defend them. This process was accompanied by revolutionary ideologies. It was at that time that Che Guevara came to Bolivia and the miners were willing to support his ideas. They killed him, but his spirit survived in Bolivia and a more revolutionary religion arose. The Oblates, together with the Jesuits, lead this movement. They wanted to defend human rights and improve the living conditions of the people; but they could not, because since 1969 in Bolivia there had constantly been dictatorships and coups d’états.

- Given this new pastoral shift, what was the attitude of the politicians?

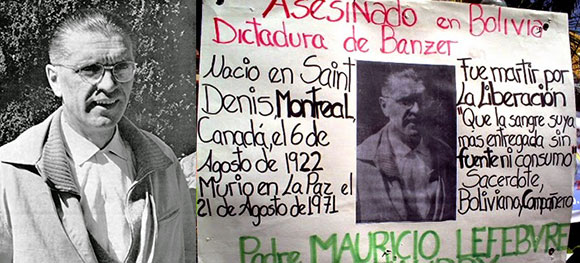

Many Oblates were persecuted. While the dictatorship of Hugo Banzer Suárez was being installed, in 1971, Fr. Mauricio Lefebvre, who had been pastor in Llallagua and then in La Paz, on August 2, 1971, was killed during the massacre of the coup. Mauricio was going in a Red Cross ambulance to help the wounded and when it approached, they riddled it with bullets in the middle of the street. The next day at the funeral, against the orders of the Government, all the people went to the cemetery. Since then, they call Fr. Mauricio a “Martyr of National Liberation.” The Oblates have never been violent people; they have been sensitive to the sufferings; they have always been close to the people.

- The dictatorships disappear and the era of democracy arrives. What do the Oblates do?

Several Oblates: Gregorio Iriarte, Gustavo Pelletier, Roberto Durette … in the years 77-78, committed themselves to the struggle of the people; they supported the women’s hunger strike and made sure that the President, a dictator, called elections.

Thanks to the efforts of the Oblates, along with other religious, supporting the women, they managed to get elections called and establish democracy. Those years were not easy. But thanks to that, in Bolivia, since 1982, we have a democracy that has brought us something more peaceful.

During this period, the Oblates have continued to work with the farmers, supporting them, teaching them to read and write, supporting production and organization efforts. These were very positive times and we were very happy accompanying the life of the people.

- They closed the mines, so now what?

IIn 1986 the neoliberal economic model arrived, a program that President Victor Paz took up, saying: “Bolivia is dying.” Then he passed Law 21060. The people will never forget. With that decree, he implanted in Bolivia the neoliberal model which closed all the mines and factories in the country. More than 30,000 workers went to the streets and many people walked to the capital, the Oblates along with them. They joined in the demonstration that was heading to La Paz, but they were unsuccessful. They were stopped and forced to return to their places of origin. But that started the crisis. For the Oblates, who had always worked with farmers and miners, when the mines closed, a vacuum, a crisis was created. The situation greatly saddened them, for now our people migrated to the cities. So they tried to open another mission in Cochabamba. The Oblates were already in Cochabamba, but we wanted to close the parish and open another mission, and maybe go to the City of Alto, a new city where several people had moved. The Oblates began to look for other areas and to initiate new experiences in 86-87. They opened soup kitchens and there arose establishments such as the “Happy Child” organization to welcome children abandoned on the street or around the area of the eastern zone of the Santa Cruz parish. We went there because there were many marginalized children who had nothing to eat. That organization continues today.

- And for the children and the mothers?

In downtown La Paz, today there is the Center for Popular Culture, with different focuses, this time for women. It aims at productive projects for women and at the defense of the human rights of women.

In another parish in Oruro, there is the Center for the Study of Andean Peoples, for the study of climate changes, collateral damages caused by mining and “environmental liabilities.” Today one would say “the aftereffects of mining.” This center is also responsible for investigating the Aymara culture, the Andean culture, and it has begun creating discussion centers on the cultural richness of the Aymara. In Cochabamba, another organization has been created: the Development Center of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. The objective of this organization? It is dedicated to distribution of media, to governance, to the development of leaders and defending human rights. The organization continues to work among women. There currently are 18 groups of women in several neighborhoods of the city of Cochabamba, in order for women to take leadership and to defend their rights.

The Oblates have always been dedicated to supporting the Church, but in the missionary sense of accompanying people in their lifestyle, in their needs, and in improving their quality of life.

- You have completed 60 years of presence in the country. During this time, what would you highlight as the most remarkable?

The Oblates have worked in what is called evangelization and inculturation, because if it is true that when they arrived, they tried to evangelize this communist and drunken atmosphere, always faithful to our motto: “I have been sent to evangelize the poor” and “the poor are evangelized,” the experience of these years shows that the Oblates have been evangelized. We’ve all experienced that, although we are announcing the Gospel to the people, we receive a lot from the people. Most of the missionaries admit that the inculturation of the Gospel results in the missionary’s learning too; he does not remain passively contemplating culture or handing on the faith, because in handing on the faith, the culture is handed on to him. Our inculturation process in recent years reveals how we have been evangelized by the people. When we see a mother, who is caring for nine children and, in order to feed them, she has to work; when we see how this woman is able to give her life for others; or when we see a leader committed to the social struggle for human rights, in the pursuit of better days for the people, these are examples of why many Oblates say: “We are being evangelized.”

Interviewer: Fr. Joaquin Martinez Vega, OMI

July 2014

General House, Rome

Evangelizers being evangelized

Evangelizers being evangelized