- The first Canadian Oblate

- The right-hand man of Bishop Guigues of Bytown-Ottawa

- A painful transition

- In the service of the diocese of Saint-Boniface

- The valiant centenarian

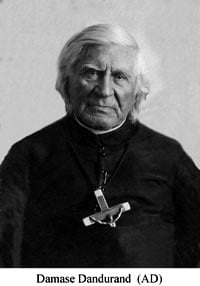

Born: Laprairie, Lower Canada, March 23, 1819

Priestly ordination: Montreal, September 12, 1841

Took the habit: Saint-Hilaire, September 24, 1841

Vows: Longueuil, December 25, 1842 (No. 104)

Died: Saint-Boniface, April 13, 1921.

Damase Dandurand was born in Laprairie, Lower Canada, on March 23, 1819. His parents were the notary, Roger François Dandurand and Marie Jovite Descombes Porcheron. The boy was precociously intelligent and he went to an English school in Montreal, during which time he stayed with his uncle who inspired him with a taste for architecture. He continued his education under tutors and finished his classical studies in the college in Chambly. Having chosen to become a priest, he taught while studying theology. He was then recalled to Montreal in 1840, spending some time in the major seminary and, for a time, he was assistant to Bishop Forbin-Janson who was then visiting Canada. He received the sub-diaconate on August 30, 1840, the deaconate on September 5, 1841 and was ordained to the priesthood, with a dispensation on account of his age, on September 12, 1841. The ordaining prelate was Bishop Rémi Gaulin of Kingston.

The first Canadian Oblate

When the first Oblates from France, whom Bishop Bourget had obtained from Bishop de Mazenod, arrived in Montreal on December 2, 1841, Father Dandurand was resident in the bishop’s house. Shortly afterwards he decided to join them and he began his novitiate on December 24, probably in Saint Hilaire. The following year, at Christmas, he took vows in Longueuil. Bishop de Mazenod rejoiced to have found in him “the first fruits of this good country of Canada.” Starting in 1842, he took part in numerous missions or retreats in the diocese of Montreal and his ministry was specially appreciated by the English speaking Catholics. Also in 1844, he spent some weeks on two occasions visiting the townships of the East.

When the Oblates took over the pastoral care of Bytown, in Upper Canada, Father Dandurand was sent, in the month of May, to assist Father Telmon among the Irish community. On that occasion he addressed a long letter to the Founder, revealing his talent as a shrewd observer of the region. On the arrival of Father Malloy, he returned to preaching in the area of Montreal (1845-1847).

The right-hand man of Bishop Guigues of Bytown-Ottawa

Because of an outbreak of typhus, Father Dandurand returned to Bytown in July 1847 to help the overworked personnel. Struck down himself, he retained horrible memories of the event. On his recovery, Bishop Guigues, who had now become the local Bishop, appointed him to be pastor of the cathedral parish of Notre- Dame, a function that he continued to exercise from1848 to 1874. Each year the parish registers list between 270 and 514 Baptisms, between 54 and 149 marriages, and between 104 and 376 burials, and that in spite of the fact that the parish was sub-divided on a number of occasions. The pastor established numerous associations, supervised the charitable and educational works of the Grey Nuns, and obtained the cooperation of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Since Father Molloy and others continued the ministry among the Irish, the pastor now took care mainly of the Canadians, that is, the French speakers.

Besides this ministry he also had a number of commitments in the service of the diocese. Having been officially the bishop’s secretary for ten years, he was vicar general of the diocese (1862-1874) and several times administrator, notably in 1870-1871 during the Vatican Council. He kept a close watch on the building of the cathedral. It was he who corrected the placing of the side windows, who saw to the building of the two towers and who had the nave lengthened by the addition of a deep apse. At the same time he attended to the lesser needs as well as to the great ones. He has been accused of being attached to his titles, which may reflect a lack of self-confidence and the need to be appreciated.

The Oblate community had taken up residence in the bishop’s house in 1850 and it was there that Father Dandurand spent twenty-five years. Continually overcharged with work and obviously not a model of regularity, he was the perpetual first councillor of the superior. He was also provincial procurator from 1856 to 1862. The Oblate authorities were often critical of Bishop Guigues and uneasy about the legal consequences of the administration of the vicar general. In 1870 they discontinued the agreement that defined the role of the Oblates in Ottawa, while continuing to leave him to serve in the diocese. He was at ease with the little people who made up the majority of his parishioners, but he did not shirk the company of the mighty and we find that he was, to a greater or lesser extent, involved in the developments which changed an ill reputed slum into the capital of the country.

A painful transition

Before his death on February 8, 1874, Bishop Guigues made known to Father Dandurand that he would be appointed administrator of the diocese, sede vacante. He had also recommended him as the most worthy to succeed him. “For the twenty-five years of my episcopate, the one most devoted to the diocese and to me personally, he was my right hand, my consolation, one who was my other self during my long and frequent periods of absence.” The Oblates were opposed to one of them being appointed and the Canadian episcopacy took account of that. For Father Dandurand it was a painful experience and the open opposition to Bishop Thomas Duhamel, who was appointed on September 1, added to his dismay. Nevertheless he took care of the ordination ceremony and he initiated the new bishop in his office. Without doubt he nurtured the hope that he would be able to remain in Ottawa, which in the circumstances, would have been impossible.

In January 1875 he withdrew to the Oblate residence in Hull and his troubled condition became increasingly obvious. He had declared that he wished to become a Cistercian and, under a pseudonym, he had requested dispensation from his religious vows. Bouts of loyalty to his house alternated with painful outbursts of self-deprecation. At one point, when his mental condition was misunderstood, his erratic behaviour was severely criticised in both Paris and Rome. The condescending attitude was that because of his “thoughtless character” and “being merciful in his regard”, it was decided to keep him in the Congregation.

Bishop Duhamel had suggested, as a diversion, that he take a trip to Europe and Father Dandurand set out at the end of May. He was well received in the general house and was pleased with his excursions in Paris and its surroundings. As part of the plan to keep him at a distance from Canada, it was suggested to him that he minister in the Anglo-Irish Province, but he replied that he would not be able to do so. Since Archbishop Alexandre Taché of Saint-Boniface had already approached him, he received an obedience for Manitoba and he arrived there at the end of August 1875.

In the service of the diocese of Saint-Boniface

His first assignment was to Winnipeg where the Oblates ministered to about one thousand Catholics. Father Dandurand felt useless and victimized. Father Fabre, who understood him better than others, helped to appease his feelings but the storms continued and left him feeling diminished and disillusioned. Soon afterwards, he undertook the care of a little parish with about 50 families, Saint Charles of the Assiniboines. It was composed mostly of Métis and there, from 1876 to 1900 he exercised an unspectacular but much appreciated ministry. His priestly golden jubilee and the fiftieth anniversary of the Oblates in Canada in 1891 occasioned a visit to Eastern Canada and a solemn demonstration of appreciation was organized in Ottawa by Bishop Duhamel. In 1894, he had himself the joy of receiving Father Louis Soullier, superior general, in Saint-Charles. When Bishop Adélard Langevin spoke of withdrawing him from his parish, Father Dandurand expressed the wish to return to the East rather than “die completely useless”. He was in his eighties when the archbishop offered him the hospitality of his house and the chaplaincy to the children and the aged in the care of the Grey Nuns (in the Taché hospice and later in the Youville Hospice). There he was held in veneration and his numerous jubilees were celebrated with affection. He was glad to reside in archbishop’s house (1900 to 1916). It was a milieu in keeping with his tastes and his capabilities.

The valiant centenarian

It was not until fourteen months after the death of Bishop Langevin that, at the age of 97, he became resigned to give up ministry and seek much-needed health care among his brothers in the Juniorate in Saint-Boniface. Even though he enjoyed good health in his old age, his hearing deteriorated and his movement became more uncertain. He dictated his Memoirs to Father Adrien Morice, fell in line with the regular life of the community, kept up with the news of the war, studied the new Code of Canon Law and he liked to chat and keep up his correspondence. Influenza had interrupted the preparations for his centenary, but Archbishop Arthur Béliveau wanted to make the occasion a diocesan as well as an Oblate feast. The jubilarian celebrated Mass in public twice, was present at the celebration gatherings, took part in the banquet and spoke on several occasions. He received from Pope Benedict XV the faculty to impart the papal blessing in the cathedral on the day of the celebrations, which was March 25, 1919. He then wanted to reach the eightieth anniversary of ordination. He was within five months and eight days of his 103rd birthday when he died in the juniorate of Saint-Boniface on April 13, 1921, having been bed ridden for only ten days previously. His funeral was held in the cathedral on the 16th and was presided by Archbishop Olivier Elzéar Mathieu of Regina in the absence of Archbishop Béliveau. Burial was in the juniorate cemetery.

His priestly life, as he himself was well aware, was divided into two parts: one was very active in which he fulfilled important roles, the other had very little influence apart from a little country parish and a community of Sisters, old people and orphans, on the periphery of the evolution which was changing the face of Western Canada. At least he had succeeded in gaining peace of mind and his memory is that of a tender and generous old man, who was both loved and admired.

Émilien Lamirande