- Origins of the Shrine and the Pilgrimage

- The Oblates at Notre-Dame de Lumières in 1837

- The Good Years (1837-1880)

- Parish Missions

- The Juniorate

- Crisis Years (1880-1922)

- The renewed presence of the Oblates from 1922 on

The shrine of Notre-Dame de Lumières is situated between Avignon and Apt in the parish of Goult 50 kilometres north of Aix-en-Provence.

Origins of the Shrine and the Pilgrimage

Already in the 4th century, on the spot where the actual crypt stands, there stood a chapel dedicated to Our Lady. The Cassian hermits who had their hermitages in the surrounding valleys used to assemble in this chapel to pray. Very well attended during the Middle Ages, it was abandoned and almost entirely destroyed as a result of the wars of religion of the 16th century.

In August of 1661, an old man from the parish of Goult, crippled by disease, Anthony of Nantes by name, dragged himself to the vicinity of the venerated ruins. Suddenly, he saw “a great light” and in the midst of that light, “the most beautiful child one could imagine.” The crippled man drew near. He reached out this arms, but the vision disappeared. At that very moment, he was cured of a hernia “of extraordinary size and distension.”

As a sign of appreciation toward the Blessed Virgin, the Christian people rebuilt the ancient chapel from its ruins. The crypt was finished in 1663. The Carmelites, who arrived the following year, undertook the construction of the church we see there today. The function of the church was to stand over the crypt and preserve it. On September 13, 1669, Bishop J.-B. de Sade de Mazan, bishop of Cavaillon, consecrated the church under the title of “Mother of Eternal Light.”

Pilgrims came in crowds and many people were healed right up until the Revolution. At that time, the Carmelites were forced to leave. The church and the convent were put up for auction as state property and was bought back by the Lord of Goult. Then, in 1823, it was bought by the Trappists of Aiguebelle. The stay of the Trappists at Lumières was very brief. Diocesan priests took on the responsibility of ministry at the shrine.

The Oblates at Notre-Dame de Lumières in 1837

Bishop de Mazenod himself gave an account in his diary entries of January 26, May 30 and June 9 of the history of the Oblate foundation of Notre-Dame de Lumières.

Already in 1821, the vicar general of Avignon, Mr. Margaillan, had suggested to Father de Mazenod that the Missionaries of Provence should take on the responsibility of missions in the Provençal language in the diocese. By common agreement, however, it was decided to postpone this project to a later date because the local Catholics had raised some money for an establishment of the Jesuits which was due to take place in 1824.

At the end of 1836, the Trappists, desiring to rid themselves of their property offered to sell the church and convent to Bishop de Mazenod so as to establish an Oblate community there. They had already made contact with Bishop Celestin Dupont, the archbishop of Avignon, who was at the origin, it seems, of the idea of making this suggestion to the Oblates. He knew of the Oblates through the missions they occasionally preached in his diocese and through Father Dominic Albini, a classmate of his at the major seminary in Nice from 1810 to 1813.

The purchase agreement for the property was negotiated December 14, 1836 by Father Henry Tempier and Father Isidore Pastorel. For the sum of about 20,000 francs, the Congregation became owners of the shrine of Notre-Dame de Lumières.

June 2, the first Friday of the month and feast of the Sacred Heart, the Founder, Father Tempier and Father Jean-Baptiste Honorat, appointed first superior of this tenth Oblate community, officially took possession. They had arrived on the scene May 30. Within a few days, they had “examined both the house and the garden foot by foot” as well as the church which the Founder found to be “very beautiful size and of a good kind.”

The act of appointing the superior bears the date of June 2. On June 9, Bishop Dupont signed the letters of the canonical installation of the Oblate community and assigned them the task: 1) of being custodians of the shrine of Notre-Dame de Lumières in order to continue to carry on there and to give even wider diffusion to devotion to the most holy Mother of God and to provide good guidance for the piety of the faithful who came to that holy place from all parts of the diocese and even beyond. 2) of evangelizing all the parishes of our diocese, either by parish missions or by spiritual retreats in response to the requests made to them by the parish priests or upon the directions given them by myself. 3) giving spiritual retreats to priests or to other churchmen who would feel comfortable in going there to draw apart for a few days of recollection in the shadow of the shrine of the Blessed Virgin.”

The Oblates would be faithful to these several ministries. In addition, they would make of Notre-Dame de Lumières an important house of formation and would always maintain there a large community which the Founder and the Superiors General loved to visit and whose fraternal charity they often praised. Like all Oblate communities in France in the last century, this community whose numbers would never fall below ten priests and brothers, saw a frequent turn over in personnel because of frequent departures for foreign missions. This characteristic of rotating personnel held true as well, to a lesser degree, for the thirty superiors who succeeded each other in the course of a century and a half, and held office on the average for a little less than five years each. A few Oblates used to uphold the traditions, especially Fathers Pierre Nicolas (1812-1903), Eugène Le Cunff (1843-1934) and in particular Jean Françon (1807-1883) who exercised his ministry there for some forty years.

The Good Years (1837-1880)

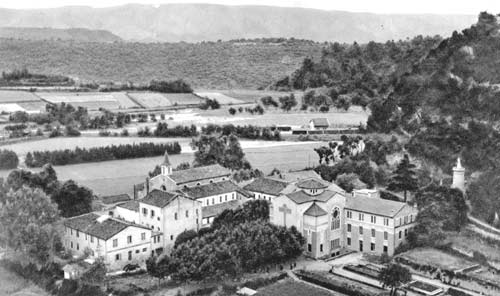

After the arrival of the Oblates, Notre-Dame de Lumières was for a few years a construction project for material transformation of the site. Everything was run down. The convent was threatening to collapse and the roof of the church as well as that of St. Michael’s chapel on the hill-side were on the point of caving in. It was there that Father Honorat acquired the habit of wielding the “damn trowel,” a habit he kept up in Canada that drew down upon his head some harsh reprimands from the Founder. Father Tempier, deeply impressed at the quantity of water that flowed from the Imergue and the Calavon laid out some fine gardens and planted hundreds of trees.

The Pilgrimage

While they were working at the material restoration, the Oblates also worked to achieve spiritual renewal. In Missions of 1863, we read that, in a few years, they brought back to Lumières “droves of pilgrims” and restored to the pilgrimage “its brilliance of yesteryear.” (p. 490-491)

The annual number of pilgrims generally hovered around 50,000. A few thousand came for the feast of the Blessed Virgin celebrated August 15 and September 8 or yet again that of the Archangel St. Michael on September 29. Twenty thousand were present at the feast of the crowning of the Virgin on July 30, 1864. In addition to these extraordinary gatherings, pilgrims used to come all summer, starting with the month of May; they came singly or in groups organized by parishes, confraternities and schools.

What characterized these pilgrimages is the fact that the main events took place at night, recalling the lights which were the original attraction for the flood of pilgrims. There were torch-light processions right up to the oratory of St. Michael, sermons, confessions, open air Masses, etc.

Miracles, less frequently than in former centuries, continued to bolster confidence in the intercessory power of and twenty-five of them.

Parish Missions

The Oblates replaced the 17th century diptych of miracles-pilgrimages with the mission-pilgrimage diptych. Faithful to the main ends of the Congregation, the Oblate priests were on ministry campaigning already in the month of October and would only return for the pilgrimage season in May-June.

From 1862 to 1880, the review Missions devoted several pages every year to listing the missions preached by the priests of the provinces of France as well as a narration of the events more worthy of note and the more outstanding successes. In the last issue of 1863 (p. 491) we read that from 1837 to 1863, the four or five mission preachers from Notre-Dame de Lumières gave 129 missions, 30 jubilees and 118 retreats in the dioceses of Avignon, Valence, Aix and Digne.

Next, it noted some thirty ministry events per year up until 1866. That year, wrote Father Françon in the codex historicus “the time for parish missions is over; the parish priests no longer request missions except for Easter.” The priests noticed as well that “secret societies are making inroads all over.” (Missions 5 (1866), p. 586-588) and, in addition to that, four other communities were now preaching in the diocese whereas in 1837 the Oblates were the only ones engaged in this ministry.

Towards 1870, the community of Lumières was almost entirely at the service of the juniorate, but two or three priest still went to preach, especially preach retreats. They “are not called to preach in the grand pulpits,” wrote Father Auguste Bermès to Father Joseph Fabre in an October 2, 1870 letter, “they do not have occasion to exercise their zeal on a grand stage and their preaching does not create in the world the stir that brings human glory, but they are happy to dedicate themselves to the original work, the work that is basic to our dear Congregation. It is to the poor that God sent them; it is the poor that they evangelize.” (Missions, 9 (1870), p. 515)

From 1870 to 1880, there remained only two preachers to respond each year to about ten requests for missions or retreats. (Missions, 11 (1873), p. 286; 17 (1879), p. 336)

The Juniorate

Notre-Dame de Lumières was almost always an Oblate house of formation. That is what won for it the title of “second cradle” of the Oblates. (Missions, 14 (1876), p. 113) For all practical purposes, there were five juniorates.

The first was established from 1840 to 1847. It seems that the initiative was taken by Father Pierre Aubert, a member of the Lumières community, and his brother Casimir Aubert, the master of novices.

It was without enthusiasm and as a last resort that the Founder granted his approval for this trial project. In his diary entry of August 13, 1840, he wrote: “I gave my consent that they should try to take in a few students since the novitiate has no regular source of supply, but I am not hiding from them the little confidence I have in a means that takes so much time and is so uncertain with regard to finding candidates. At my age, I cannot allow myself the delusion of thinking that I will see the fruit it produces.”

They received a few young men for the three final years of the classical course for 1841-1842, then between fifteen and twenty each year following that. They wore the cassock. It seems the Superior General became convinced little by little of the benefit of this endeavour. In 1841, he allowed them to add one story on the convent and observed that the trial project carried out “is most encouraging. All the young men who make up the student body of this house of studies,” he wrote in his May 12, 1841 diary entry, “are inspired by the best spirits. They burn with the desire to be judged worthy of being admitted to the novitiate.”

Father Jean-Claude Léonard’s recruiting tour in 1847-1848 proved so successful that the novitiate of Notre-Dame de l’Osier was filled with seminarians, seventy in one year. Father Tempier, the treasurer, was no longer able to come up with the money needed to support so many young people in formation. In December of 1847, the General Council was forced to demand the closure of the juniorates of Lumières and Notre-Dame de Bon Secours.

The project had proven promising enough and, in this case, Bishop de Mazenod did not prove to a be good prophet. He did, in fact, see thirty priests emerge from this juniorate, several of whom became foreign missionaries, such as Bishop Henri Faraud, the first junior, and Fathers Joseph Tabaret, Charles Arnaud, Eugène Cauvin and Jean-Pierre Bernard, missionaries to Canada, Édouard Chevalier to the United States, Augustin Gaudet to Texas, Joseph Arnoux to England, Joseph Vivier to Ceylon, Casimir Chirouse and Charles Pandozy to Oregon, etc. The superiors themselves set the example. Indeed, Father Jean-Baptiste Honorat, the first superior, was the founder of the Oblate missions in Canada, Father Pascal Ricard, the second superior, founded the Oblate missions of Oregon and Father Pierre Aubert, the first director of the juniorate, was the first Oblate sent into western Canada with the scholastic brother, Alexandre Taché.

These young men also learned to love the Congregation and its Founder. That is where his first biographers received their formation, namely Fathers Toussaint Rambert and Achilles Rey. And even Father Robert Cooke can be listed among them. As a scholastic brother, he spent his summer vacation there in 1845.

The second juniorate remained open from 1854 to 1882. It was in 1859 that Father Casimir Aubert, provincial of Midi, with the authorization of the General Council, decided to open a juniorate at Lumières to better furnish candidates for the novitiate. Father Célestin Augier, the superior who was appointed, initially received a few students of the last three years of classical studies. Beginnings were slow. In 1866, there were still only sixteen juniors, but the number grew to thirty-five in 1868 and to forty-five in 1869, with a full contingent of courses and a teaching staff of seven priests.

At the time of the Franco-Prussian war, in the fall of 1870, the students were sent home to their families for a few months; then, life soon revived with forty juniors. Father Joseph Fabre, the Superior General, visited the juniorate in October of 1872 and “found there that the juniorate was more brimming with life and more fervent than ever.” At the time reading in the refectory was from Mélanges historiques by Bishop Jacques Jeancard and it was the sole topic of conversation. (Missions, 10 (1872), p. 703)

In 1878, the young students of the first two forms were sent to Notre-Dame de Bon Secours. At the time, the house had produced fifty Oblates in twenty-three years.

Crisis Years (1880-1922)

The concordat of 1801 did not mention religious congregations. Since that time a lot of orders had been reconstituted and a number of Congregations had been founded without having received legal recognition from the state. They became the scapegoats of the lay policies which took hold from 1880. On March 29, a decree from the French government dissolved the religious bodies dedicated to teaching or who were friends of the Jesuits.

On November 5, 1880, the priests were expelled from the house by the police. Some friendly parish priests gave them shelter. The superior and three priests obtained authorization to remain as custodians of the convent. The church was officially closed to the public, but a passage was left open between the convent and the crypt. It was later closed as a result of being reported.

During the summer of 1882, the juniorate was obliged, in turn, to close its doors because it was judged to be in contravention of the Falloux law of 1850 with regard to secondary education. The juniors were initially received at the minor seminary of Beaucaire in the diocese of Nîmes; then, in December 1883, they were sent to Diano Marina in Italy.

In 1886-1887, a two-fold calamity. On October 26, 1886, a few violent downpours caused the Imergue to swell over its banks. Water flooded the crypt; the classroom roof collapsed and the walls around the yard were undefmined. In Italy, an earthquake struck on February 23, 1887, and destroyed the house at Diano Marina claiming two victims among the juniors.

The priests returned little by little and continued preaching. Missions noted forty-four ministry endeavours from 1882 to 1884, one hundred and thirty-five from 1884 to 1887 and twenty-five missions, eight Lenten series and one hundred and thirty seven retreats between 1887 and 1893, but the shrine remained officially closed.

The juniors returned to Lumières with a Mr. Bonnard, a university graduate, a layman who was an exemplary Christian as head of the institute. This third juniorate remained open from 1887 to 1901 with an average annual student body of fifty students and it provided four or five novices per year.

A new and a more serious anticlerical offensive was launched in 1901. All the religious congregations were subject to making a request for legal recognition. From that point on, the provincial judged it wise to send the juniors back to their homes and families or to send them to Notre-Dame de Sion. In 1903, the Oblates’ request for legal recognition was rejected as were almost all the requests submitted by religious congregations. On April 7, the chief of police of Apt notified the Oblates that they would be required to vacate their premises in two weeks time and that Lumières would become state property.

According to the law of July 1, 1901, the liquidators were obliged to sell by auction the confiscated property they had seized. At Lumières, a certain Mr. Duez, the liquidator of the Oblate properties, was in no hurry to carry out his administrative duties. The sale was set for April 7, 1908. In 1901, the prefect had written to Paris that the property was worth 100,000 francs. The liquidator fixed the minimum price at 28,000 francs. At the first auction of April 7, no buyer presented himself to purchase the property. The second auction was set for June 23 and the price was lowered to 16,000 francs. In collaboration with the Oblates, Bishop Élie Redon, the vicar general of Avignon, bought the property. Significant repair work was undertaken at that time. Then, under the direction of Abbé Sage, the pilgrimage, officially reopened on August 15, 1909, immediately revived.

From 1916 to 1920, the Archbishop of Avignon entrusted the shrine to the Assumptionists (under the title of the diocesan missionary association) and allowed them to set up a minor seminary.

The renewed presence of the Oblates from 1922 on

After the 1914-1918 war, the government officials became more tolerant. A more moderate Chamber of Deputies favoured closer relations with the Vatican in 1921. Given these favourable circumstances, the Oblates bought back the shrine for 20,000 francs. On September 8, 1923, they received 4000 pilgrims who came to celebrate the feast of the Virgin. Right up until 1960, pilgrims continued to come. The feast of September 8, in particular, persisted in its form and its traditional grandeur. It was usual to see 3000 to 5000 pilgrims, except during the war years and these most recent years. Other celebrations, as well, drew pilgrims such as the 1964 centenary of the crowning and the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the Oblates in 1987.

The house received once again, this time for the fourth time, juniors from 1922 to 1928. They subsequently left Lumières to go to Lyon and gave over the house to the scholastic brothers of Midi province who came from Liège. A new construction and a new chapel, dubbed the Mission chapel, would be built for them in 1930.

About fifty scholastic brothers were enumerated there each year until 1939. At the beginning of the war, the residents of the house numbered one hundred and twenty with the arrival of forty-six Polish scholastic brothers, forty-eight priests and brothers from the province Est and twelve members from the province Nord. Father Victor Gaben, the provincial, and the two successive superiors, Fathers Louis Perruisset and Joseph Reslé, had to work and to dedicate themselves without counting the cost to nourish and educate all these people. This number subsequently fell little by little: about seventy in 1943 and 1944, fifty-seven in 1947; it, then, fell regularly to the level where it was no longer practical to maintain a professorial staff. In 1951, the scholastic brothers joined their confreres of the Nord in Solignac.

When Father Hilaire Balmès made his canonical visit of the house in April of 1942, he wrote that Lumières could no longer remain a scholasticate because of the too large number of pilgrims and foreigners who regularly flooded the house and the gardens.

In 1957, the provincial authorities decided to open the fifth juniorate. Under the direction of Father Jean-Pierre Eymard, a few children from the countryside attended classes for the first years in preparation for the advanced classes at the Franco-Canadian school (junior college) of Lyon. The pilot project lasted only two years.

It seems that mission preaching did not take hold again in Lumières as it had in other Oblate houses in France for about fifteen years after the war. On the other hand, the community of Lumières took on two other kinds of ministry: parishes and a hosting service.

Already before 1940, but especially during the war, many parishes were left without priests. The professors from the scholasticate and even the scholastic brothers were asked to replace the parish priests on Sunday. This ministry continued after the closure of the scholasticate. In 1980-1981, of the twelve priests in the house, only one was assigned to ministry at the shrine. The others were involved in receiving guests and often served in eighteen churches in the surrounding parishes.

Hosting retreats had already been foreseen in the canonical letters of installation issued by Bishop Dupont in 1837. When the Oblates returned in 1922, they began to host retreatants in that part of the house dubbed the guest quarters. In the report of his canonical visit in the fall of 1936, Father Théodore Labouré wrote: “As for the retreat house, given the present circumstances, they have done well to dub it the guest quarters. That is hardly what it is; that is certainly not what it should be.”

When the juniorate closed about 1960, the house was more oriented to receiving retreatants: receiving children preparing for their profession of faith or confirmation, receiving members of Catholic action, hosting various activities related to the life of the diocese of Avignon: catechetical days, sessions on pastoral issues, priests councils, etc.

From 1972 on, significant repairs were called for because of the age of the buildings. Today, some fifteen priests and brothers are still assigned to this house. Some of them, further on in years, are retired; the others share in three kinds of activities: pilgrimage, parish work (the group of parishes cared for by two priests consists of sixteen parishes) and hosting events: tourism, meetings, organized trips and thirty day de Mazenod experience.

Yvon Beaudoin, o.m.i.