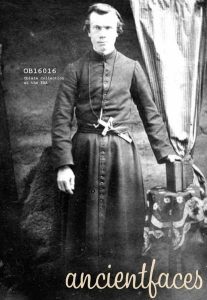

Constantine Scollen in 1873

Born: Galloon Island (Newton Butler, County Fermanagh), Ireland, April 6, 1841.

Took the habit: Aug. 14, 1858.

Vows: Aug. 15, 1865 (N. 657).

Priestly ordination: April 12, 1873.

Died: Dayton, Ohio, USA, Nov. 8, 1902.

Scollen was called Con during most of his life. Although he formally left the Oblates in July, 1885, after 26 years as an Oblate, Archbishop Adelard Langevin, OMI, was convinced that Scollen always remained an Oblate at heart, and made him an honorary member. In several ways, he surpassed Fr. Albert Lacombe, OMI, his mentor in working with Canada’s First Nations. He witnessed the tragedy of the change in the Native Americans of the plains of Canada and the USA, as the buffalo were exterminated by the Europeans, practically every treaty broken, and the Canadian Government forced the children into European style schools, where their language and culture were destroyed.

Scollen was born on Galloon Island, Ireland, on April 6, 1841. His parents were Patrick and Margaret Scollen (nee Margaret McDermott). He had a younger sister, Rose, and brother, Hugh. His mother died during the Potato Famine, when Con was 6. Jonathan Ryan noted in 2017 that he was “surrounded by hunger, poverty and desperate pleas for intervention–experiences that would play a part in his life’s work.”

His father moved from Ireland to England, there marrying Catherine McEvoy, finding work as a warehouse-man in a silk mill in Bradford, West Yorkshire. Con’s two half-brothers, John and William, were born there. About 1855, the family moved to Crook, County Durham, where his father worked in a coal mine and two half-sisters and four more half-brothers were born.

Scollen received a classical education at Ushaw College. Although his tutor, Father Brook, hoped he would continue his studies in Rome, the fact that a much older cousin, Thomas Louis Connolly, a Franciscan Capuchin, had become Archbishop of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1854 seems to have directed his attention to Canada.

Since two of his friends had joined the Oblates, Scollen entered the novitiate in Sicklinghall, England, on Aug. 14, 1858. He made his first vows as a lay brother on Aug. 15, 1859 (there is some evidence that a lack of money in his immediate family led to his being a lay brother and not a scholastic). He was sent to the retreat house Glenmary, in Inchicore, south of Dublin, Ireland, and began his 26 years as an Oblate. There he taught, but what subjects is a mystery. The novitiate moved from England to Glenmary, Ireland, towards the end of 1860, and Scollen went with it.

He was fluent from his infancy in both Gaelic and English. During his studies he became fluent in Greek, Latin, Italian, and German. Since the official language of the Oblates at this time was French, he probably began learning French before going to Canada. With almost all the Oblates in western Canada French speaking, he became proficient in that language too. His main biographer, Ian Fletcher, states “he had an extraordinary talent for languages and became the foremost linguist in the Oblates in Canada” (all further quotes are from Fletcher unless otherwise noted). He may have taught classical or modern languages to the novices.

In March, 1862, he left Ireland and returned to Yorkshire, making vows as a lay brother for a five year period on March 25, 1862. In April, he and an Irish Oblate scholastic traveled with Oblate Archbishop Alexandre-Antonin Tache, arriving in St Boniface, Canada on May 26, 1862.

Father Albert Lacombe, OMI, then took Scollen under his wing and introduced him to the cultures and languages of Canada’s Native Americans. He made his perpetual vows as a scholastic on Aug. 15, 1865. He opened an English language school for the children of the employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company, at nearby Fort Edmonton. This was the first elementary school in the Northwest Territories. A famine and the dispersal of the families closed the school in 1868.

Working with Fr. Lacombe on the Cree dictionary and grammar, he also taught Cree to new missionaries as they arrived at St. Albert, Alberta, 1868-72. During this time he also lived among the native peoples on the prairies, while continuing the study of philosophy and theology under Fr. Vital Fourmond, OMI. Bishop Vital Grandin, OMI, ordained him to the priesthood on April 12, 1873.

Already fluent in both Cree and Chippewa (Ojibwe), he now began his ministry with the Blackfoot, which language he quickly learned and taught. By the time he left the Oblates, he also spoke and taught Sarcee, and Assiniboine. The author of the article on Scollen at the Glenbow Museum, notes that he served as superior of the Southern Oblate Missions until 1882. He remained mainly among the Blackfoot and Kainai Blood people on the plains of Southern Alberta and Northern Montana, living their hard nomadic life without a break, apart from brief spring and autumn visits to St Albert, for supplies and to Fort Macleod.

In 1876, he was one of two unofficial interpreters on behalf of some of the Plains Cree Chiefs as the Canadian Government negotiated Treaty 6. Bernice Venini states that Scollen’s recommendation that a missing Cree chief, who was out hunting, was essential for the treaty, resulted in the lieutenant-governor of Manitoba requesting the chief’s presence. That chief’s name (Sweet Grass) heads the lists of chiefs on the treaty. In 1877, he was an unpaid consultant to the government prior to the signing of Treaty 7 with the Blackfoot Confederacy, again serving as an unofficial interpreter and witness.

Scollen was very much aware of the Sioux in Nebraska, USA, the massacre of General Custer, and the attempt by the Sioux to have the Blackfoot join them in “an alliance offensive and defensive against all white people in the country.” At the request of the lieutenant governor, he sent a detailed description of the difference between the Cree and Blackfoot in their dealings with whites.

Ryan, during his long interview in 2017 with Marvin Yellowbird, one of the Samson Cree chiefs, was urged by Yellowbird to learn about Scollen as a model of positive influence by the white man. Scollen “displayed no interest in converting them into ‘good subjects of the Crown,’ as he would say sarcastically in many of his letters. Scollen saw exactly what that meant in his native Ireland.”

Ryan also notes: “Although he did want the First Nations people to be Catholics, he didn’t want them to eradicate their culture. He wrote: ‘I said I had to learn the Indian languages in order to instruct the Indians. The missionary who attempts to convert Indians through an interpreter or by trying to teach them his language, or by spreading bibles and pamphlets broad-cast among them, as I have known some evangelical societies to do, is simply losing his time, and is guilty of an imposition’.”

Scollen’s half-brother William came to western Canada in 1877. William’s troubles added to the stress that Scollen was already experiencing from living so much with the native peoples, from defending them from the national government, and from jealousy from other Oblates. Lacombe’s plagiarizing of much of Scollen’s work has been documented by Fletcher.

The Red River Resistance of 1869-70 and and the North-West Rebellion of 1885, both led by Louis Riel (during part of this time, Riel stayed with the Oblates in Plattsburg, NY, USA), caused tremendous stress to Scollen. Riel’s hanging by the national government on Nov. 16, 1885 was not the last straw, but close to it.

A bout with cholera and his very slow recovery added to the pressure in 1883. The final straw was probably the yearlong insistence up to Jan. 7, 1883, from Cree and Stoney leaders, that he help them draft a letter to government leaders calling attention to their dire poverty and utter destitution during the past severe winter. All treaty promises for food had been broken.

Government leaders immediately accused Scollen of instigating the letter. He replied very thoroughly to regional newspapers that he had simply put the Natives plea into the proper form. Bishop Grandin thoroughly investigated the government’s complaints and exonerated him.

On Aug. 13, 1885, Scollen wrote to the governor general of the Northwest Territories, explaining his decision to leave the Oblates , “being the only Irishman, my existence among them has been unbearable.” The governor general did “strongly recommend” that he be paid “a small amount of money, say 150 dollars which would represent three months pay at 50 dollars a month, the time during which Father Scollen remained and worked in the interest of the Gvt and country and did a great deal towards keeping the Indians quiet.”

In early Dec., 1885, Scollen asked to be readmitted to the Oblates. He was told to complete a second, year-long novitiate at the novitiate of the First American Province, USA, Tewksbury, MA. At the end of three months, he left, writing from the Oblate “College de Ottawa,” Canada, to the superior general, “it costs me more than I can say to leave this Mother but I am compelled to do this because I no longer find myself strong enough to make a years novitiate after twenty-four years of very active work in wild country.” During his time in Tewksbury, he was able to visit a cousin, Margaret Cruddens, in nearby Lowell, MA., where many Irish and French Oblates ministered.

He returned to western Canada and served there as a diocesan priest, working under Oblate bishops, from June 1886 to January, 1887. He asked to go to work with Native Americans in the Dakota Territories, USA, and received the necessary document stating that he was a priest in good standing. He was asked to take a parish of four languages: English, French, and two Indian languages. He spoke all four, and spent two productive years there.

From 1889-92, under the direction of his bishop, he moved to St. Stephen’s Mission, Fremont, WY, now on the Wind River Reservation of the Arapaho. He immediately began learning the language (his sixth Native American language), then writing a grammar and vocabulary to aid others.

In June, 1892, the bishop asked him to administer the cathedral in Cheyenne for a month. Then he was appointed as pastor of St. Joseph Church (in the process of building) in Buffalo, Johnson County, WY. During the severe winter of 1892/93, his recurring TB laid him low.

By the spring of 1893, he had recovered, and was sending sections of his autobiography to a local newspaper, the Buffalo (WY) Bulletin, which found them fascinating. Unfortunately the manuscript itself has been lost. Fletcher has found 42 of the newspaper articles , which he estimates at about two-thirds of the original manuscript. Fletcher has published them in a comprehensive book The Search for “Thirty Years Among the Indians of the North West,” A Work by Constantine M. Scollen, Missionary Priest.

Father Roger Buliard OMI’s famous work Inuk is a classic for both anthropology and adventure in serving the Eskimo. Scollen’s autobiography, as recovered by Fletcher, equals it for serving Native Americans.

After 186 pages of letters, Fletcher added Scollen’s The Arapahoe Language, Alphabet and Orthography, 1891 (52 pp), which shows Scollen as a master linguist. Scollen sent much of this to the Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives in Washington, DC, USA, where some of it was lost. He is the only Oblate to have materials at the Smithsonian. Some of this material was published by Frs. Lacombe and Legal under their names, as were many of Scollen’s earlier language studies and reports.

In late 1893, his health failed again, and the bishop moved him to St. Joseph’s Church, Rawlins, Carbon County, WY. There are no letters or records of the year he spent there.

In October, 1895, he moved to St. Mary’s Church, Orleans, Harlan County, NB. The more temperate climate noticeably lessened his chronic rheumatism. Although there were no Native Americans there, there were plenty of European immigrants, and Scollen’s knowledge of languages proved very useful.

In early 1897, Bishop Hennessy of Wichita, KS, asked him to help the pastor at Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Concordia, KS. There he met again some of the sisters who had been teaching at St. Stephen Mission, Fremont, WY, when he was there.

St. Patrick’s Day, 1898, found him on the balcony of the archbishop’s residence in Chicago, IL, watching the parade enthusiastically with other clergy. From June, 1898 until late 1898, he travelled in the Eastern USA States, conducting missions on behalf of Native American Missions. He visited Lowell, MA, again.

Then he worked as an assistant priest in the parishes of St. Joseph, Dayton, Immaculate Conception, Kenton, and St. Mary, Urbana, all in Ohio, also conducting parish missions throughout the state. He fell ill in mid-1902 and was nursed by the Poor Sisters of St. Francis at St. Elizabeth Hospital, Dayton, Ohio. He died there on Nov. 8, 1902.

The tuberculosis which had afflicted him for many years was the cause of death. During his funeral Mass, the celebrant said that Scollen “was recorded in the register of the Oblates of Mary as one of the most Brilliant Stars, for his indefatigable zeal among the Indians.” The nuns who nursed him considered him a saint, “totally unassuming in all his ways.”

Harry Winter, OMI