- Introduction

- Durban (1852 – 2004)

- Pietermaritzburg (since 1852)

- Saint Michael’s Mission (1855-1856; 1858-1860 and 1882 - 1890)

- Seven Sorrows Mission (1860-1861)

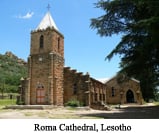

- Roma, Lesotho (since 1862)

- Conclusion

Introduction

The period under consideration in this study is 1852 when the Oblates first arrived in Natal until the death of the Founder in 1861. It therefore describes the growth of the mission in Southern Africa during the Founder’s lifetime. The period mentioned above was one of trial and tribulation to establish the mission among the Zulus, but was eventually marked by the success of the mission among the Basotho after the death of the Founder and for that reason the mission in Roma, Lesotho, is included in this study despite the fact that is falls just after the dates that we are considering. It is nevertheless important so as to complete the story of the early missionary attempts of the Oblates in Southern Africa.

In the spring of 1850, Bishop Barnabò, then the secretary of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, requested Bishop de Mazenod to send Oblates to South Africa. This mission presented two advantages: the Apostolic Vicariate would be Oblate and the Oblates could evangelize the pagans. The Founder immediately accepted and recalled the Oblate Fathers from Algeria where the bishop, Bishop Pavy, and the civil authorities were against working with the Muslims.

Durban (1852 – 2004)

Bishop Jean François Allard, ordained bishop by Bishop de Mazenod in Marseilles on 13 July 1851, and the first group of Oblates, Fathers Lawrence Dunne and Jean-Baptiste Sabon, Deacon Julien Logegaray and Brother Joseph Compin, arrived in Port Natal on 15 March 1852, and the first mass celebrated with the local Catholics was on the 19th March 1852. On the 1st April 1852, the Bishop and his group of missionaries left for Pietermaritzburg in the interior.

Fr. Sabon was appointed as the parish priest of Durban in December 1852. He opened the first Catholic Church in Durban on 24 July 1853. Later, a larger church was built on the same site and opened on 13 November 1881. Finally, the present Emmanuel Cathedral was established in 1902.

Despite his difficulties with English and Zulu, he eventually experienced great success in Durban, and even managed to learn Tamil, as he developed a great apostolate among the local Indian community. When Fr. Sabon died on 15 January 1885, his parish stretched along the coast from Verulem to Umzinto

On a macro level what was the Vicariate of Natal in 1886 was divided into three sections to establish the Vicariates of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. The Vicariate of Natal was divided once more in 1921 to create the Apostolic Vicariates of Mariannhill, Eshowe and Swaziland. In 1958 there was a further division of the Vicariate of Natal, which had become the Archdiocese of Durban (1951), so as to establish the diocese of Dundee. These are some of the major divisions that have taken place since the Oblates first arrived in Durban on the 15thMarch 1852.

Perhaps, it was only fitting that the Oblate presence at the Cathedral in Durban ended with the late Bishop Denis Hurley, who died on the 13 February 2004 as a result of having suffered a stroke. He had opted to retire at the Cathedral, so as to build-up the inner city parish to something of its former glory, while he served as administrator of the parish in his last years. During this period, the Cathedral (built in 1902) was renovated in preparation for the celebration of the Jubilee Year in 2000.

In terms of the Oblate presence in Durban over the years, by 2005, out of a population of 3,000,000 people, 212 468 were Catholic, due to a large extent to the efforts of the Oblates. The parish of the Assumption, in Umbilo, was dedicated perpetually to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

Pietermaritzburg (since 1852)

Within the first week of April 1852, Bishop Allard and his confreres established themselves at Pietermaritzburg, a city 89 kilometres northwest of Durban. Straight away they constructed a chapel which was blessed on the 25th December 1852.

It was in that very same chapel that Father Joseph Gerard was ordained to the priesthood on the 19th February 1854. He began learning Zulu together with Father Justin Barret.

After his first missionary attempts to evangelize the Zulus at St. Michael’s mission, Fr. Barret remained at St. Mary’s as parish priest (1856-1906). Here he achieved great success in the parish and in the administration of St. Mary’s Parish School. He taught in the school and was assisted for many years by only a female teacher. Within the parish, he worked among the Irish who were either soldiers or workmen. He also visited the surrounding areas of Pietermaritzburg on horseback and had the distinction of having been the parish priest of St. Mary’s for fifty years. Father Barret was the Oblate who had worked most closely with Joseph Gerard in establishing the initial missionary attempts by the Oblates in the evangelization of the Zulus.

St. Mary’s has been in the care of the Oblates from the beginning in 1852 until the present day, so it is for this reason that it is worthwhile mentioning the parish priests who have served at St. Mary’s Parish. These are the gallant men who have served to provide continuity within St. Mary’s Parish from the time of the Founder until the present day.

- 1852 – 1856 Father Julien Logegary

- 1856 – 1906 Father Justin Barret (50 years)

- 1906 – 1911 Father Auguste Chauvin

- 1911 – 1936 Father Armand Langouët (25 years)

- 1937 – 1942 Father Charles Wolf

- 1943 – 1946 Father John Gannon

- 1947 – 1955 Father Angus McKinnon

- 1956 – 1959 Father Raymond Coates

- 1960 – 1965 Father G.T. Carrington

- 1966 – 1969 Father Thomas Slattery

- 1970 – 1980 Father Basil Miller (10 years)

- 1980 – 1996 Father Eric Boulle (16years)

- 1997 – 1998 Father Jabulani Nxumalo (now Archbishop of Bloemfontein)

- 1998 – 2007 Father Mario Cerutti.

An outstation of St. Mary’s that is of tremendous importance when discussing Pietermaritzburg is St. Anthony’s, which was established in 1862, and was at that time served by Father Justin Barret. In 1886, Bishop Jolivet bought a wood and iron building that measured 30 feet, and was situated at the corner of Loop Street and Retief Street. This building was used both as a school and a chapel. The bishop appointed Father Vigneron as the priest in charge of St. Anthony’s Mission. A new parish priest was appointed in 1887, viz. Father Chauvin, who began fundraising so as to build the present day church. It is unclear from the records whether the building was begun or was completed in 1901; however, it was Father Valette, who was appointed in 1905 that saw to it that all the outstanding debts for the building of the Church had been paid off. Fathers Leo Gabriel and Claude Lawrence were ordained in St. Anthony’s Church in 1934, and Father Gabriel served as parish priest for 24 years (1935 – 1959). In 1959, while Father O’Sullivan was parish priest, the parish was divided as a result of the socio-political conditions in the country and the implementation of the apartheid laws. The buildings at St. Anthony’s were abandoned and it was only in May 1980 that a decision was taken to renovate the parish under the leadership of Father Reginald Shunmugam, who had been appointed parish priest in 1979. Father Shunmugam was the last Oblate to serve at St. Anthony’s. He handed over the pastoral care of the faithful to the Franciscan Capuchins. At present the parish is in the pastoral care of the Missionaries of St. Patrick, the Kiltegans.

Saint Michael’s Mission (1855-1856; 1858-1860 and 1882 – 1890)

The decision to begin a mission at Dumisa’s Kraal resulted from a council meeting held on 2 January 1855. It was Bishop Allard who favoured the idea of beginning a mission within the then existing British Colony. In this regard there was agreement from the two missionaries, Joseph Gerard and Justin Barret on the need to begin the mission about 100km southeast of Pietermaritzburg. On 27 February 1855, the two missionaries set out with enthusiasm and hope for the success of their new mission. Bro. Bernard was sent to assist them in building a few huts, after some controversy had emerged concerning the payment to local workers for the building of huts.

The first chapel was blessed on the 2nd September 1855, which marked the official opening of the mission at St. Michael’s under the patronage of the Archangel. The missionaries had begun teaching the local people hymns in Zulu and invited them to frequently visit the chapel. Unfortunately, the seasonal rains caused some damage to the roof of the chapel and there was a continuous problem with dampness.

Much more devastating, however, was the attack on the mission by about three hundred of Chief Dumisa’s men on 25 May 1856. The missionaries took the matter up with Bishop Allard, who sent a memorandum to Theophilus Shepstone, the Secretary of Native Affairs. Shepstone placed the matter in the hands of Magistrate H.F. Fynn, who investigated the matter on 28 June 1856 and in turn sent copies of statements made by witnesses to Shepstone. The decision was taken that the Amacele and the tribe of Chief Dumisa were both to be fined for the trouble that had ensued.

On 17 July 1856 it was decided to abandon the mission, as the Amacele had fled the area and were unlikely to return. This meant that the area around the mission had become deserted and the missionaries were then left on their own. This failure caused great concern to the Founder: “Not a single one of those poor infidels to whom you were sent, has yet opened his eyes to the light you are bringing them!”( To Allard, St. Louis near Marseilles, 30 May 1857, quoted in Leflon, Eugene de Mazenod, IV, 2, p..234.) To make matters worse, Cetshwayo and Mbulazi, the sons of Mpande (1840 – 1872) quarrelled over who would be heir to the throne and civil war broke out in December 1856 thereby worsening the problem of refugees fleeing from the violence. Finally, King Mpande was succeeded by his son Cetshwayo in 1872.

The second attempt to evangelize the Zulu at St. Michael’s mission was a combination of spiritual training and industrial training. By industrial training, it is meant an attempt to establish a trade school. This in turn was based on the hope and presumption that the Native Land Commission would grant a piece of land for that purpose. On 15 February 1858, Fathers Joseph Gérard and Victor Bompart made another attempt to re-establish St. Michael’s mission. Some of the trials that they faced initially were a shortage of wood for building purposes and sickness among the cattle. The new chapel was opened on 17 July 1859 and the Sunday services were kept simple: they were comprised of two hymns, a sermon and a recitation of the litany to the Blessed Virgin Mary. The Zulus appreciated the presence of the Oblates, but showed no signs of conversion to Christianity. Their attachment to customs such as polygamy were among the chief obstacles for the lack of conversions. After a year there were signs that the people had become harder of heart and that they had stopped the females from attending catechism. However, 1860 was not the end of the attempts of the Oblates to evangelize the Zulus at St. Michael’s mission.

After the Oblates had been expelled from France on the 2nd November 1880, a number of young French and Irish clergy were sent to Natal during the 1880’s. These young clergymen included Fathers Crétinon, Follis, Hammer, Howlett, Kelly, Mathieu, Murray, Porte, Trabaud, Vernhet and Vigneron. They decided to re-open the St. Michael’s mission, as it had been inactive since 1863. A mission initiative was embarked on after 1881, as there was now more staff; however, there were still financial restraints that plagued the success of the mission. The Oblate General Council expected some degree of success from the new missionary impulse and injection of new personnel into the life of the Natal mission. Above all, they thought that St. Michael’s mission could be re-opened with a minimum of financial outlay. Consequently, Fathers Mathieu and Baudry were sent to re-open the mission on 12 June 1882. The two priests carried a letter from the bishop to the chief, and were expected to consider the possibility of re-establishing themselves at St. Michael’s. After the two priests discussed the condition of the mission with the bishop, they were given authority to re-open the mission. Brother Tivenan was sent to assist the new project by helping with the building. By 6 September 1882, a telegram was sent to the bishop indicating that the attitude of the people was favourable. Bishop Jolivet visited the mission in November and suggested that a dam be built and a wind-mill erected to help with irrigation. Father Baudry was transferred from St. Michael’s to Umtata in April 1883.

In January 1884 Father Barthélemy was transferred from Lesotho and took up residence at St. Michael’s in Natal. In turn, Father Mathieu was transferred to the mission at Oakford in March 1884. Despite the initial promising reports about Barthélemy’s success in learning the Zulu language, and the large numbers of children in the school, the mission at St. Michael’s did not flourish under the leadership of Father Barthélemy. As a result, the care of the mission was placed in the care of a layman, Baron de Pavel, in 1887 and the mission was eventually handed over to the care of the Trappists in 1890.

Seven Sorrows Mission (1860-1861)

Bishop Allard and Joseph Gérard had the idea of re-establishing a new mission among their original parishioners, the Amacele, who by that time had settled in Umzimkulu. This third attempt to open a mission among the Zulus was at Our Lady of Seven Sorrows (1860-1861). On the 17th July 1860, Bishop Allard, Father Joseph Gerard, and Brothers Bernard and Terpent, set out to establish a mission among the Amacele. The Amacele welcomed them and gave them a hut as a temporary dwelling; however, the return of the Oblates among them came as a surprise. When they collected wood for building, the Chief Maketiketi protested as a sign of showing his continued authority over the tribe. However, the building continued and the new chapel was blessed on 14 October 1860. The ceremony was attended by approximately 120 people. Brother Terpent had made a harmonium that served to accompany the singing. By April 1861, they had not been approached by any adults for baptism, after ten months of missionary effort, and still they faced a complete lack of success. The Zulu were also very suspicious when the missionaries spoke to the sick. Brother Terpent caught his foot in a trap while attempting to replenish their meat supply, and it took a long time to have him returned to the capital for medical treatment. The death of the Founder was announced in August 1861 and, by that time, the Oblates had decided to abandon their third missionary attempt among the Zulus. It was evident that the Zulus were happy enough to have the Missionary Oblates live among them, but their primary option was to remain living as pagans without having to make drastic changes to their culture or to change their customs too much. The year 1861 marks the end of the Oblate mission at Our Lady of Seven Sorrows.

Roma, Lesotho (since 1862)

After having returned to Natal, Joseph Gérard and Brother Bernard again left for Lesotho and arrived at Roma on 11 October 1862, where they started building a cottage. They renamed the valley Motse-oa-’M’a-Jesu, viz. the Village of the Mother of God which later became known as Roma. The first chapel was completed by 1 November 1863. The Oblate mission among the Basothos had begun and the explosion of converts to Catholicism that the Founder had hoped for was about to be ignited.

The social structure of the Basotho was different from that of the Zulus in that the communities are found in villages and not independent clans with large tracts of land that separate one homestead from another. This meant that, as a people, they were more peace loving and were easier to gather together. The Basotho were made up of smaller clans that had joined together after being pushed westward by the Zulu armies that were seeking to amalgamate these smaller groups into the Zulu Empire.

The willing reception of the missionaries by King Moshoeshoe was another helpful factor that contributed to the success of the Oblate mission in Lesotho. The Basotho had protestant missionaries living with them before the Oblates arrived, and among other issues, they had become tired of what was referred to as the “interfering nature of the ministers’ wives” in social affairs. Moshoeshoe as king maintained that it is better for a sick person to be served by two doctors, rather than just one doctor. In this way he delayed his baptism, so as not to be seen as one-sided. Thus, he could play the missionaries off one another for his own advantage and ensure progress and development for his people.

The contribution of the Holy Family Sisters should not be overlooked in this regard, as the development offered by the schools and hospitals started by the Sisters was part of the broader reason why Moshoeshoe wanted the Catholics to work among his people in Lesotho. The Sisters also taught house-skills, developed herbal remedies and taught weaving with wool, which assisted the welfare and economy of the ordinary people. In many ways, the Basotho can be described as having been more ready to receive the message of the gospel and to be evangelized. The soil was well prepared for the seed of the gospel to be sown, so as to reap an eternal harvest.

Conclusion

It is fitting to ask the question: “What were the differences of the Oblate mission in Lesotho as opposed to the first attempts to evangelize the Zulus?” It is true that the Oblate missionaries were more accustomed to preaching parish missions than engaging in first evangelization of the indigenous peoples of Africa. The Zulu people to whom they came to preach the gospel were a strong and proud people, who did not accept what the missionaries preached to them as being what they were seeking on a spiritual level. The Zulus were also accustomed to victory in war and violence was part of the culture of survival in their traditional environment. The nest of tribal faction fighting into which the missionaries found themselves embroiled, during the early years of the mission, was highly unsettling. The people to whom they were ministering would of necessity have to be on the move constantly, as a result of the violence within the society. To understand this process better, it is important to understand the social context within which the early Oblate missionaries had to evangelize these indigenous people for the first time.

The Mfecane (1815-1840) is a Zulu term which means the “crushing” or the “scattering”. This describes the movement of indigenous peoples from the eastern seaboard, in a southwesterly direction, towards the Transkei and the Cape. What was the cause of this movement of people and why did friction result from this process of migration? One of the main reasons was the introduction of maize into Mozambique by the Portuguese. Maize, as compared to the traditional millet and sorghum, was more drought resistant and created a more secure source of food, which caused the population to increase. The water sources for cattle usage had reached a premium and there was pressure to find more land and water for the herds of cattle. This problem of water shortage was further exacerbated by the ten-year drought that took place in the early 1800’s. These factors, combined with the rise of the Zulu kingdom under King Shaka (1812-1828), meant that tribes had to engage in war in this process of the expansion of the Zulu kingdom. Tribes that were unwilling to be amalgamated into the Zulu kingdom were forced to flee.

The Oblates mission in Natal can be described as a success in the long term, despite the initial setbacks that were not anticipated given that the missionaries were engaged in first evangelization. The success in Lesotho served as a vindication of the efforts of the missionaries. However, the Paris Mission Society had done significant work. The concepts and mentality of Christianity were not totally new to the early converts, thus the task had been made easier. However, the constancy of effort and the depth of faith imparted to the people of Lesotho bear testimony to the unrelenting efforts of Joseph Gerard and the first Missionary Oblates who arrived in South Africa in 1852.

Alan Henriques, o.m.i.