- First foundation (1849-1851)

- Second foundation: building a missionary center (1852-1858)

- Mexico (1858-1866)

- The Crisis: Lost Hope in Paris, Internal Division in Texas (1866-1883)

- The First U.S. Province: “Permission to Live,” Barely (1883-1903)

- The Second U.S. Province: Daughter Parishes, Social Segregation, End of the Horseback Era (1904-1923)

- Focus on the City: Filial Chapels, Gradual End of the Ranchero Ministry (1924-1964)

- Cathedral of New Diocese, Church of the Poor (1965 - present)

First foundation (1849-1851)

In 1849 Father Adrien Telmon, assuming that he was still authorized to make an Oblate foundation in the United States after the failure of the attempt at Pittsburgh, accepted the request made by Jean Marie Odin, the first bishop of Galveston (Texas), for the Oblates to extend the presence of the Texas Catholic church into the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Taking with him Fathers Gaudet and Soulerin, lay brother Joseph Menthe, and scholastic Brother Paul Gélot, Father Telmon temporarily sent Father Gaudet and Brother Gélot to Galveston with Bishop Odin while he and his other two companions took the boat from New Orleans to the mouth of the Rio Grande. Landing at Point Isabel on December 3, 1849, they continued on to Brownsville, thirty miles distant, two days later.

Since Brownsville was a new town on the north bank of the Rio Grande, the river that had just become the international boundary between the United States and Mexico as a result of the United States war against Mexico in 1846-1848, there was as yet no Catholic church or religious residence. One or the other outlying ranch already had its own family chapel, but the people on what had just become the Texas side of the river had traditionally depended for religious services upon the priests in the Mexican city of Matamoros just across the river. Given its location on the new international border where the Rio Grande flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, Brownsville with its port of Point Isabel was from the beginning an important commercial and administrative center for the entire Lower Rio Grande region of Texas and Mexico that stretched above it along the Rio Grande. As such, especially in the initial years in which United States political, civil, and economic structures were just being established in the region, it drew many European and American adventurers with little interest in religion into what had been and remained a traditional Mexican Catholic rural countryside.

At the beginning the three Oblates struggled with very little support, even from the Mexicans who traditionally gave much respect to priests. The Oblates attributed the Mexican’s initial diffidence to their hearing the priests speaking in English, halting as it was, which the Oblates said made the Mexicans believe that the priests were not really Catholic. Just as important if not more so may have been the fact that a vagrant Irish priest had been in Brownsville before the Oblates’ arrival, and his bad conduct had led the people to oust him. After three months the Oblates lost the use of the building they had been loaned for a chapel and they could not afford a raise in their lodging fees. Hoping the townspeople would be taught a lesson, the missionaries gratefully accepting the hospitality of a devout French American officer and his family in the adjacent U.S. military garrison for six weeks. During their stay with the military, the people of Brownsville had no Mass available since the general public was barred from entering the garrison. During that time the priests traveled upriver to minister to the other new U.S. military posts on the international border, probably by way of the steamboats that plied the Rio Grande since the U.S.-Mexican War. Bishop Odin had entrusted the Oblates with the pastoral care of the entire county extending 75 miles upriver and an even greater distance northward along the Texas coast. Though the priests apparently were unable to visit most of the county, they found solace in the pious welcome, which they received, in their weekly trips to the Marian chapel in the nearby village of Santa Rita, inhabited by traditional devout Mexican Catholics.

Very gradually, as civil order improved and the missionaries began to learn Spanish, they gained more people’s confidence in Brownsville itself. They were able to recommence celebrating Mass in town on Holy Thursday in a small house lent to them for free, and by the end of June they managed to buy some property on credit and build a small wooden church they named St. Mary. They regularly held separate church services in English and Spanish. By September they were beginning the construction of a boy’s school and hoping to obtain women religious to build one for girls. Ironically, just as things were looking more promising, the Oblates’ earlier letters from Brownsville and Galveston describing the dire conditions in both places had finally reached France. Unaware of the recently improved prospects, the General Council decided to recall to Canada Father Soulerin in Brownsville and Father Gaudet in Galveston, leaving Father Telmon solely responsible for the work in Brownsville. After Soulerin’s departure November 14, Father Telmon continued to minister until he felt his isolated position was no longer sustainable with his weakened health. He finally departed on January 22, 1851.

Second foundation: building a missionary center (1852-1858)

Bishop Odin was deeply disappointed, but not about to give up. Sorely in need of priests, religious, and financial support, he embarked on a European tour in 1851. In Marseilles, he implored the Founder to come to the aid of Texas with two principal objectives: to return to the Rio Grande Valley and to begin a college-seminary in Galveston. Bishop de Mazenod responded generously with the largest group of missionaries he had ever sent at one time, six priests and one lay brother. They were all very young, ranging from 24 to 34 years old. For superior he chose Father Jean-Marie Verdet, ordained only three years, with the other five priests ordained in February 1852 just prior to their departure and Brother Pierre Roudet having just made his profession in December. These seven men had a long and profound impact on the Oblate mission in Texas, where they all remained until their deaths. Four of them labored until the end of the century: Fathers Hippolyte Olivier, Pierre Parisot, Étienne Vignolle, and Brother Roudet; two others, Fathers Jean-Marie Gaye and Pierre Kéralum, ministered thirty and twenty years respectively.

Since the Rio Grande country was reportedly in turmoil due to a revolution on the Mexican side of the river – an experience often repeated in future years – Bishop Odin had all the Oblates proceed initially to Galveston. They arrived in May 1852 and dedicated themselves to studying English and Spanish while helping with ministry needs. Father Gaye quickly demonstrated a special gift for the Spanish language and the Mexican culture; he became the pioneer Oblate in all but one of the new mission initiatives of the Oblates among Mexicans in Texas and Mexico for the next thirty years. Fathers Gaye, Verdet, Olivier, and Brother Roudet departed for Brownsville in October. In February 1853 Father Kéralum and Father Barthélemy Duperray, a diocesan priest ordained in France who became an Oblate postulant in Galveston, also transferred to Brownsville. Traveling with them were the Sisters of the Incarnate Word and Blessed Sacrament, recruited by Bishop Odin from France to start the first Catholic girls’ academy in the Rio Grande Valley. They and their school are still in Brownsville today. The Oblates themselves briefly conducted a simple school for boys but soon suspended it after Father Duperray died in an epidemic in early 1855; they asserted that this ministry had an adverse affect on the health of the Oblates who taught in it.

From the beginning, the Brownsville house also became a novitiate for French-origin diocesan priests who asked to join the Oblates and for Brother candidates from among the Mexican people. But Father Duperray, another young French priest who became an Oblate, and the first Mexican novice for the Brotherhood all died during epidemics in the 1850s. In the 1860s one Mexican novice for the Brotherhood left after three months, another was not approved for vows, and an older French diocesan priest left his novitiate after four months. There is no known record of other postulants until the 1890s.

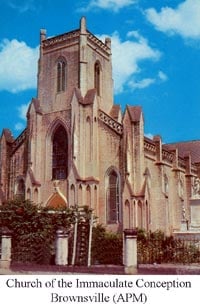

Father Kéralum, an architect and carpenter by trade before entering the Oblates, was probably transferred to Brownsville not only to assist in pastoral ministry, but also in view of the need to help Father Verdet, himself a skilled builder, and Brother Roudet to construct residences, churches, and schools in the vast Brownsville mission district, beginning with that city itself. Between 1853 and 1861 the Oblates built the Sisters’ convent and school, the church of the Immaculate Conception, which became the mother church of the Brownsville mission territory, and finally their own residence. The neo-Gothic church and ample rectory are still in use today.

As the Founder himself later wrote, the new parish foundation in Brownsville was meant to be a missionary center to the surrounding countryside and villages of what were then the large counties of Cameron and Hidalgo (now subdivided into Cameron, Hidalgo, Willacy, Kenedy, and part of Brooks counties). As their numbers increased the Oblates began longer and longer circuits visiting places along the Rio Grande and in the interior country that they learned to call “La Costa,” since it paralleled the Gulf Coast (La Costa) for over 100 miles northward. In 1853 they accepted the bishop’s request that they expand their mission territory further west along the Rio Grande to include Starr County, where Father Gaye established a missionary residence in the town of Roma in 1854. But when Father Verdet traveled to France in 1855 to ask for more Oblates, the response from the General Council was to order the withdrawal of the Oblates from Roma as soon as the bishop of Texas could send a priest there. Father Kéralum, the last Oblate in Roma, handed the parish over in June 1856. The timing was fortuitous in one sad sense. Father Verdet drowned in a shipwreck off the Louisiana coast in August 1856, while acquiring materials for the church construction in Brownsville. Having just left Roma, Father Kéralum was on hand in Brownsville to finish Father Verdet’s project.

When the Oblates decided to remove themselves from the school ministry in Galveston in 1857, the Brownsville mission was supposedly the beneficiary, particularly with an eye toward expansion into Mexico. Five of the seven religious in Galveston were transferred to Brownsville, including Father Gaudet, who had been sent back to Galveston in late 1856 as the new superior of the Texas Oblates upon the death of Father Verdet. The others were Fathers Parisot and Vignolle, from the original band sent from France in 1852, and Father de Lustrac and Brother Copeland, both of whom had joined the Oblates in Galveston. But no sooner had Father Parisot arrived in Brownsville in October 1857 than at the bishop’s urgent request he and Father Gaye were sent to temporarily take charge, respectively, of the English and Spanish-speaking Catholic churches of San Antonio during the European absence of their pastor. The Oblates hoped that the bishop would decide to keep them in this important city, but it was not to be. Father Gaudet as superior in Brownsville occupied himself mostly with administrative and internal Oblate affairs, supervising but not actively engaged in the external ministry.

Mexico (1858-1866)

Thus it was only when Fathers Gaye and Parisot returned to Brownsville after May 1858 that there were more than three or four priests available for ministry there for the first time since the establishment of the Roma residence in 1854. After Father de Lustrac died in another epidemic in October 1858, there were still five priests, all from the original 1852 band, under the direction of Father Gaudet. Although this was little more than the bare minimum needed to care for the Spanish-speaking and English-speaking congregations in Brownsville and regularly visit all the outlying villages and ranches in Cameron and Hidalgo counties, the Oblates leapt at an offer that was made to them at this time. For several years they had been receiving requests to provide assistance to the very few clergy in the large city of Matamoros directly across the Rio Grande and in other Mexican border towns. After leaving Roma, Father Gaye had temporarily assisted the pastor of Matamoros, Father Músquiz, in December 1855 and January 1856, before being sent on an extended collecting tour in Mexico to benefit the construction of the Brownsville church. Upon his return from San Antonio in mid-1858, Gaye was asked by the Matamoros pastor, who was also the ecclesiastical dean of northern Tamaulipas, the Mexican state that included all the border towns, to preach a one-month mission in one of the interior towns. Upon the conclusion of the mission, Father Gaye was asked to take over responsibility in actuality but not in title of the huge parish of Matamoros itself, since the pastor himself was looking toward retirement.

Bishop de Mazenod had always fervently hoped that the Rio Grande foundation would have important consequences for Mexico itself. The Oblates accepted the administration of Matamoros, where Father Gaye remained until the end of 1864 with the help of various assistants. In late 1860-early 1861 Father Parisot provided pastoral care to the temporarily clergyless town of Reynosa sixty miles upriver on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. Whereas Father Verdet had been unable to obtain any additional Oblates for the Texas side of the Rio Grande mission in 1855, the actual fact of the Matamoros ministry and solid invitations to staff other places in Mexico finally prompted the Founder to send two priests, François Sivy and Joseph Rieux, in December 1859 and three more – Jean Eugène Schumacher, Jean Maurel, and Jean-Marie Clos – in 1861. Sivy and Schumacher would die in yet another epidemic in 1862, but the other three became that many more longtime laborers along the Rio Grande.

With this solid reinforcement, the veteran Father Olivier took the newly arrived Father Sivy with him in 1860 to take charge of the parish of Ciudad Victoria, the capital of Tamaulipas 190 miles south of Brownsville, but they were expelled at the end of the year by the Liberal authorities who had established their political dominance in Mexico. Father Gaye left the bustling and cosmopolitan Matamoros in late 1864 to assist and eventually replace the old Mexican diocesan pastor in the small town of Agualeguas, 40 miles southwest of Roma in the neighboring Mexican state of Nuevo León. This time it apparently did not matter to the Oblate authorities that this new Oblate assignment was quite remote from Brownsville, as long as it was in Mexico and near the border. Agualeguas was off any main roads, too “insignificant” for Mexican Liberals to seriously dispute a French clergy presence. Father Gaye and his eventual companion, Father Rieux, happily remained there for two decades, pastoring Agualeguas and two or three nearby towns.

Civil wars in both the United States and Mexico between 1860 and 1866, including the French Intervention in Mexico, brought not only local hardships upon the people but also maritime blockades of Texas ports which greatly increased the importance of Matamoros and its port of Bagdad. The Oblates’ sympathies, as French churchmen in the Southern United States, were with the losing side in the civil conflicts in both countries. The war conditions made communication with the Oblate superiors in France very infrequent and delayed, and also effectively blocked any transfer of personnel in or out of the Brownsville mission. With the resumption of regular communication at the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865, the Oblates of the Brownsville mission sought to further expand their work in Mexico in response to Invitations from various bishops. Protesting that the eight priests (not including the Vicar, Father Gaudet), by now mostly middle-aged, were stretched thin by their ministries at Matamoros, Brownsville, and Agualeguas and all their attached villages and ranches, and yet that the field of Mexico was ripe for the harvest, they persuaded Father General Fabre to send three more priests in late 1865, including Fathers Joseph Malmartel and Jean-Marie Jaffrès, the latter newly ordained. Hardly had these new recruits arrived, however, than the Oblates were expelled from Matamoros in 1866 by the triumphant Liberal regime. This crushing evidence of the political reality in Mexico effectively ended any more thought of ministry there for the immediate future, beyond the quasi-hidden outpost of Agualeguas. The Oblates remained willing to respond to the Mexican church’s calls for emergency help, such as when Father “Esteban” Vignolle pastored the Reynosa parish for six months in 1867.

The Crisis: Lost Hope in Paris, Internal Division in Texas (1866-1883)

With the door to Mexico closed, the local Oblates turned their eyes once more toward Texas. They were receiving invitations to expand their ministry there, and they were especially favorable to establishing a stronger base like San Antonio outside their beloved Rio Grande Valley, seemingly bypassed by the state’s progress. But with Mexico gone, the General Administration was not disposed to new foundations in Texas. They engaged in a protracted internal debate about whether or not to remain there, and eventually sought to find a way to gracefully withdraw since they considered the mission too isolated and unlikely to develop. This was even more the case when in 1874 the Vicariate of Brownsville was established, covering all of South Texas, with an American bishop coming from Alabama. The Oblates had been asked to let one of their own be the first Vicar Apostolic, but the preference of the General Administration was to withdraw entirely from this mission. They were only held back because the new bishop could not immediately replace the Oblates; if another religious congregation could be found to take over the mission, they would gladly relinquish it.

The change in attitude was evident. Whereas 23 Oblates had been missioned to Texas between 1852 and 1865, only 10 were sent between 1866 and 1883, mostly so that the Oblates there would not feel totally abandoned. The ten arrivals were almost matched by eight departures. Father Gaudet was replaced as superior by Father Vandenberghe in 1874; two of the recently arrived priests proved unsuitable; a Brother left the Oblates; and two priests brought in as teachers departed after a year. But the departure that struck the deepest nerve symbolically was the disappearance of Father Kéralum in 1872 (see Kéralum entry). During his twenty years in the Brownsville missions, “el santo Padre Pedrito” had become a beloved figure to all, laity and Oblates alike, not so much for his obvious skills in construction, but rather for his even more evident humility, gentleness, and dedication to visiting his large circuit of ranches. When he failed to return from one such tour, his unexplained loss seemed symptomatic of the discouraging times.

But at least the debate about the status of the Texas mission kept the General Council from transferring Oblates out of it unless they proved unsuitable. After the expulsion from Matamoros in 1866 there were ten priests and three Brothers crowded into the Brownsville residence, besides the two priests in Agualeguas. Their eyes naturally turned toward the upriver missions above their own Brownsville district, that is, the mission district of Roma where they had briefly ministered a decade earlier. That district now included both Starr and Zapata counties, reaching all the way up to the village of San Ignacio below Laredo. The bishop of Texas was only too happy to offer the Oblates this Roma mission, and the General Administration also “approved very readily.” In the latter’s minds, this was not really the opening of a new mission, but rather a natural extension of the Brownsville mission, and it had the advantage of placing Oblates near the Agualeguas district. With the establishment of the Roma missionary center, the territory of the Brownsville mission was actually reduced somewhat, since the dividing line was drawn at La Lomita, removing the western third of Hidalgo County from the Brownsville mission. La Lomita was a ranch with a small chapel and residence on one of two colonial-era porciónes or long narrow strips of land that had been bequeathed to the Oblates in 1861.

Yet even after three Oblates were placed in Roma, that still left eight priests and two Brothers in Brownsville. That may have seemed like a great surplus to those who did not know the realities of the mission. Seeking to disabuse them of any such impression, Father Gaudet wrote to the General Chapter of 1867. He asserted that actually the hundreds of outlying ranches were not receiving proper pastoral care due to the lack of missionaries: “To be able to answer the needs as they should be answered, it would be necessary”, he wrote, “to visit our ranchos at least every two months. To do so we would need to have at least six priests continually on the road.” Three of those six missionary circuits were in the Brownsville district, the other three in the Roma mission. The deployment of personnel in Brownsville also had to take into account both the English and Spanish-speaking congregations of Brownsville itself with its population of 10,000, the chaplaincy to the Sisters, and the little involvement of Father Gaudet himself in ministry. Even so, it would have seemed that Brownsville had enough priests for its various mission requirements.

Some Oblates had already been complaining that the real problem was Father Gaudet’s priorities. The Father Vicar, they complained, always sought to maintain a strong residential community in the Brownsville house, which meant needing more subjects there for when others were out visiting the ranches. Furthermore, Fathers Gaudet and Parisot built a finance-draining academy for boys that almost none of the other priests supported. Both the “monastic” emphasis and the academy did indeed mean less attention and resources devoted to the vast mission districts beyond the city of Brownsville, and many of the Fathers were not at all pleased. Frustrated by the refusal of the General Administration to accept other foundations in Texas, the men’s disagreements over mission priorities were intensified. Father Parisot and the two successive Oblate superiors in Brownsville, Fathers Gaudet and especially Vandenberghe, tended to emphasize trying to improve the ministry among the English-speaking or “American” congregation in the city of Brownsville, arguing reasonably that to neglect them was to neglect the future direction of the country. They were also the ones who made every effort to establish the academy for boys, St. Joseph College, again laudably endeavoring to make education more locally available for future leaders. But this meant recruiting two different teaching congregations of Brothers, neither of whom lasted long, or dedicating one or more Oblates to teaching. The latter approach included recruiting English-speaking Oblates from Canada.

In 1877 Father Soullier, a visiting assistant general, deemed that the college was a mistake given the situation in Brownsville and reconfirmed the General Council’s judgment that the Oblates should be withdrawn from Texas whenever this could be done gracefully. He ordered that the Oblates remove themselves from the administration of the college. From this time on, Father Fabre in Paris repeatedly charged Father Vandenberghe in Brownsville to find a way to accomplish the Oblate withdrawal from Texas, even though knowing that this went against the general sentiment of the Oblates ministering there.

Through it all, the Oblates continued their ministry in Brownsville and the villages and ranches of its vast mission territory. Besides the private chapels at San Rafael, San Pedro, Santa Rita, Encantado, and El Carmen along the river and Tio Cano in the interior, there was also the chapel at Point Isabel, destroyed by the departing Union army in 1864 and by hurricanes in 1874 and 1880 but rebuilt each time by the determined Father Parisot. A new chapel built at Aguanegra in 1868 by the owner of that ranch became a religious center for the eastern part of Hidalgo County. Even when the Oblates’ mission in Texas became increasingly questioned in France, the Brownsville missionaries added new chapels at opposite ends of the river road: at Santa Rosalia below Brownsville in 1877 and at Edinburgh (today’s Hidalgo) in 1879. But trial comes upon trial: the hurricane in 1880 not only destroyed the chapel at Point Isabel, but it and the flooding river in its new channel also caused the abandonment of the one at El Carmen and the loss of those at San Rafael, San Pedro, Encantado, Aguanegra, Tio Cano, and Santa Rita or Villanueva. The only two chapels that survived fairly well were the two newest ones, at Santa Rosalia and Edinburgh.

In 1882 a jewel of a little chapel was completed at Santa Maria, but from the beginning the new town it was supposed to anchor developed too far away from it. When Father Louis Pitoye was transferred in 1883 from the Brownsville mission to that of Rio Grande City (made an independent mission district from Roma in 1880), the boundary between the Brownsville and Rio Grande City mission territories was shifted further east in Hidalgo County, removing Edinburgh from the Brownsville jurisdiction. This was probably to allow Father Pitoye to continue to visit Edinburgh as he had previously done from Brownsville. This left the Brownsville mission with only the eastern third of Hidalgo County, and with only three chapels, all in Cameron County: Point Isabel, Santa Rosalia, and Santa Maria. But there were still hundreds of villages and ranches to be visited, chapel or no chapel.

And the Fathers continued, as they had from the beginning, to preach missions in other places whenever they could temporarily rearrange their personnel to make it possible. These missions were usually given by two priests, sometimes by three, and lasted from several days to several weeks. Again the first to preach a mission had been Father Gaye, but the most prominent in this type of ministry were Fathers Olivier and Clos. They had preached missions in various parts of northeastern Mexico before being expelled in 1866; afterwards they were invited to several towns and cities of South Texas.

The First U.S. Province: “Permission to Live,” Barely (1883-1903)

When Father Vandenberghe died in yet another epidemic in 1882, the assistant general Father Aimé Martinet was visiting the houses of British Columbia and quickly obtained permission to come to Texas. He urged the General Council that a decision about the Texas mission be made once and for all, and after various consultations in Texas he proposed what he termed a “radical” solution, one addressing the roots of the problem. A new United States province, he argued, should be formed by combining the prosperous establishments of the Canadian province in the Northeastern United States with the struggling but admirable Mission in South Texas. In Texas itself, Martinet drove a hard bargain with the new bishop of San Antonio, a great admirer of the Oblates who had been hoping to get them to take over Eagle Pass and its extensive mission territory along the upper Rio Grande border of his own diocese. Martinet offered to accept this further expansion of the challenging Mexican border ministry if the bishop would give the Oblates his most influential parish in San Antonio, the English-language St. Mary’s, as the strong base of support that they had always been lacking in Texas.

Father Martinet interpreted as a sign confirming his proposal the discovery at this precise juncture of the remains of the decade-long missing Father Kéralum in a remote part of the interior country: “At this decisive moment of the crisis, however, the remains of the excellent Father Kéralum, martyr of charity, … were discovered. It was as if the voice of your predecessors had said: ‘Brothers, why do you abandon us? Does the cause for which we have fallen not still remain the same?’ The Assistant General told the expectant Oblates: «You wish to have either the coup de grace or permission to live on” and prophetically he continued: “Do not expect to receive from us what we are unable to give you. Count mainly on yourselves and on the grace of God.” As it turns out, that is what they had to do. For another decade, the Oblates along the Lower Rio Grande would be left to their own resources, and those resources would even be diminished by the demands of the new province. The General Council approved Martinet’s plan, the new province was inaugurated that same year, and the San Antonio and Eagle Pass foundations were made in 1884.

In 1886, with the help of funds from the diocesan administrator, chapels were rebuilt along the river at San Rafael and Villanueva. There was also a private chapel at Naranjo. In that same year three of the Oblates at Brownsville were periodically visiting 243 mission stations, with Father “Juanito” Bretault’s vast circuit in La Costa (the interior country) termed “un vrai diocèse” by Father Parisot. The Mexican people called Father Bretault “Don Juan de la Costa,” since he spent three-quarters of the year visiting his ranches. In the Brownsville mission territory there were six chapels in all, with plans for building more. In the city of Brownsville itself one priest pastored the “Mexican” congregation, another the “American” one, and a third was the chaplain for the 30 Sisters, their 50 boarders, and 230 externs. The oldest priest, age 69, visited Point Isabel twice a month and helped at the Brownsville parish. The priests also directed the pious societies of the Hijas de Maria, the Rosary, and the Sacred Heart of Mary. Brother Roudet remained the “factotum: when he stops working, he prays.” Of the population of 20,000 in the mission territory, more than 19,000 were Catholic, of whom only 460, mostly concentrated in Brownsville, were not Mexican. That same year Father Evaristo Repiso of Brownsville joined Father Olivier, then stationed at Eagle Pass, in a three-month preaching tour in the clergyless trans-Pecos and Presidio area of West Texas. The bishop of San Antonio strongly desired for the Oblates to also take that vast district under their pastoral care, but it was too soon and too demanding right after having taken on the large Eagle Pass district and San Antonio. Two more chapels, Tampacuas and Arroyo Colorado, were built in 1888 in the interior country at a considerable distance from Brownsville; in 1890 a ninth chapel was established at Las Rusias along the river.

Even though more chapels had been built under the direction of the irrepressible Father Parisot, no help was coming from the new province or the General Administration. In fact, since 1883 the personnel situation had only worsened. Two Oblates from the Lower Rio Grande had been sent to help found the Eagle Pass mission in 1884, and another was sent in 1886. In return, during the 1880s only two new Oblates were sent to Brownsville, in fact to the entire Lower Rio Grande Valley; one was Father Repiso, the other was removed as impossible to live with soon after his arrival. In 1887 Father Clos wrote frankly to Father Martinet: “Our gathering in the North, instead of strenthening us, does nothing but weakens us.” He and others had in mind not only the diminishing personnel, but also the funds they were losing in the new provincial arrangement. In 1888 Father Jaffrés’ ill health led to his removal from Brownsville and the Lower Rio Grande missions. Once again the Oblates of the Lower Rio Grande pleaded in vain for help, but could not obtain even another lay Brother. When Father Martinet returned in 1892 to make his second official visitation, he had to tell the Texas Oblates to put aside their thoughts of creating a province independent from the Northeast U.S. in the near future, but he reassured those in Brownsville that there was “ssound hope that they would get at the suitable time abundant help from the center of the family.”

And the Oblate administration did provide more resources in one area. Father Parisot had continued to plead for Brothers, if not Fathers also, to allow the Oblates to reassume the direction of a school for boys. In his 1892 visitation, Father Martinet formally authorized Parisot to reopen St. Joseph College under Oblate direction and promised to send two Oblate assistants. The Oblates once again struggled with the school, which was basically on the primary level, since they were confronted with the free and much better funded public schools and could not provide native English-speaking staff. The school had a revolving combination of Oblate priest directors and several Oblate teaching Brothers for the next twelve years, until the Marist Brothers finally agreed in the pivotal year of 1904 (see below) to take over the institution. Under the Marists’ direction in the vastly changed socioeconomic reality of the Valley, the institution became more solid and has remained to the present day.

Father Martinet also recognized the need for more Oblate priests and more chapels to better serve the hundreds of villages and ranches of the Brownsville mission. Prompted by the bishop, he even designated La Lomita as the site of a future Oblate missionary residence between Brownsville and Rio Grande City. But increasing the number of priests was more difficult than sending teaching Brothers. Even worse, by early 1893 two of the three priests visiting the ranches had been reassigned elsewhere, but only one had been sent as a replacement, with a promise of another before the end of the year. The sole remaining veteran missionary, the aging Father Bretault, complained that in effect this left the ranches abandoned during the several months that it took for the new young French recruits to learn the languages. His missionary spirit was appalled at the consequences: “This year, almost two-thirds of the marriages were before a judge… At least 10,000 souls were unable to make their Easter duty because there was nobody to visit them… I can no longer be witness to the shameful agony of our mission.”

Fortunately, the two new priests, Fathers Bugnard and Chevrier, did become good and dedicated missionaries among the ranches, thus restoring the three missionary circuits for a short time. But the declining health of the elder Oblates caused the provincial to temporarily assign Father Bugnard to the parish ministry in late 1895, leaving Father Chevrier with both their circuits. A year later it was Bugnard who had to shoulder a double burden until help came, as Chevrier was made the director of the school. To make matters worse for the ranch ministry, there was a great drought during most of the decade. Perhaps partially on that account, the only additional chapel dedicated during this time was privately built by the Kenedys in 1897 on their La Parra ranch at the far northern edge of the Brownsville mission territory.

In Fall 1899, at the insistence of the bishop, La Lomita was finally established as a residential mission center for the Oblate ministry in all of Hidalgo County. But this only slightly reduced the mission territory of the Brownsville house, now consisting of the still undivided and thus quite large Cameron County with all its villages and ranches. This shift in territory took away two chapels, the one at Tampacuas and a brand new one at Toluca, from the Brownsville jurisdiction, but it also removed quite a few ranches without chapels. By this time, in recognition of the continued understaffing of the missions, they were divided into only two districts, and yet in 1899-1900 one of the two missionaries was also the director of the school! The “river” district between Brownsville and the Arroyo Colorado was more densely settled, while the district north of the arroyo was more sparsely settled yet much larger.

In early 1901 matters were even worse: there were only four priests for all of the Brownsville ministries including the boys’ school and the convent school, whereas previously there had been at least six, and there were only two lay Brothers for all the material work. The provincial, Father Lefebvre, was himself so concerned about the situation in Brownsville that he bluntly refused the request of the Superior General to send one of two newly arrived Oblates from France to a different destination: “Si je ne fortifie pas considérablement la maison de Brownsville, communauté, paroisse et ranches s’en vont à la ruine. Quant au collège, la présente lettre du Père Valence vous dira assez en quelle condition il se trouve.” Father Valence’s letter presented a desperate situation. That year several Oblates were sent to Brownsville, including the return of Father Bretault, the old veteran ranch visitor, who again took on the most difficult ranch circuit. With a chapel built at Los Olmales above the Arroyo Colorado in 1902 and the privately rebuilt chapel at El Carmen along the river, there were now ten chapels besides the one at Point Isabel: seven along the river and three in “La Costa,” dispersed among the hundreds of ranches.

One reason for the increasing clergy shortage was that the two generations of Oblates who had arrived along the Rio Grande before 1880, most of whom had demonstrated remarkable longevity, were finally dying or retiring from ministry. Between 1890 and 1903 nine of these pioneers died. That left only seven, all but one symbolically divided among the two original foundations: the “happy trio” of Fathers Clos and Piat and Brother Charret were still in Roma, and Fathers Pitoye and Bretault and Brother Roudet had reunited in Brownsville in 1901. After 1907 all but Bretault and Piat would be dead. Apparently since 1870 the Rio Grande Oblates had not received any new novices. In 1901 a Mexican American native of Point Isabel made his first vows as a lay Brother, but they were not renewed. There appear to have been no other novices through 1905.

Providentially for the Texas missions, finally a solution to the persistent problem of a lack of personnel was being arranged by a visiting assistant general. If Bishop de Mazenod can be considered the first patron of the Oblate missions in Texas, and Father Martinet the second, then Father Tatin, the visitor from the General Administration in 1901, completes the trinity. Tatin knew that since 1898 Bishop Forest of San Antonio had been asking that the Oblates start their own seminary in San Antonio to which he and other bishops could also send their seminarians. While in San Antonio Father Tatin learned about the interest of Archbishop Gillow in Mexico in a San Antonio seminary. In his visits Tatin carefully recorded the material and ministerial aspects of the various Oblate possessions and ministries in South and West Texas. At that time the Oblates were already ministering in seven places, all of them but San Antonio located along the Mexican border, and San Antonio was the railroad connection among them: Brownsville, La Lomita, Rio Grande City, Roma, Eagle Pass, and Del Rio. Father Tatin was especially impressed with the Oblates’ strong position in San Antonio and the prospects of the valuable La Lomita property.

With the wavering support of the U.S. provincial, and none from the latter’s council, Father Tatin vigorously pursued the proposal to found the scholasticate-seminary in San Antonio, where everyone foresaw that a new province would be formed in the near future. He saw such a scholasticate as serving to more adequately train and provide personnel not only for the Mexican border ministries in Texas and other future ministries there, but also for the foundations in Archbishop Gillow’s diocese of Oaxaca that the latter was offering to the Oblates. It was as daring and complex a move as Father Martinet’s in 1883, and the vision of Mexico was once again a primary factor as it had been with the Founder. Where would the scholastics come from? From the other Oblate scholasticates in Europe and Canada. The Oblates entered Mexico again in 1902, and the scholasticate-seminary was founded in 1903. In that same year Brother Louis Paradan arrived in Brownsville; as other Oblates came and went at Immaculate Conception Church the next thirty years, he alone would remain a continuous presence linking the “old dispensation” to the new one.

The Second U.S. Province: Daughter Parishes, Social Segregation, End of the Horseback Era (1904-1923)

The decision to undertake the San Antonio seminary, with its major financial and personnel implications, and the Mexico foundations spurred the U.S. provincial council in the Northeast to ask and obtain in 1904 that the United States Province finally be divided, creating the new Second United States Province with headquarters in San Antonio and including the new foundations in Mexico. In 1906 the novitiate which had always been at Brownsville was moved to the San Antonio seminary. But it returned to the Oblate house in Brownsville briefly between 1909 and 1912, during which time six novices were trained, before it finally found a more rural and permanent site of its own at La Lomita.

The timing for beginning a scholasticate and new provincial headquarters in San Antonio could not have been more propitious for the Rio Grande missions. In 1904 a railroad was finally completed connecting Brownsville to the rest of Texas and the United States, and it was rapidly built upriver that same year through Cameron and Hidalgo counties. Massive irrigation projects followed, transforming the formerly barren interior of those lower Rio Grande counties into nearly year-round agricultural lands. At the same time, a railroad was completed connecting the parallel towns on the Mexican side of the river with the Mexican national lines. The lower Rio Grande country was advertised as the “Magic Valley” by investors, with Anglo-Saxon Midwesterners pouring in from the north to start farms and Mexican laborers pouring in from the south to clear fields and harvest crops.

New towns sprang up along the railroad line, drawing the mushrooming population away from the old river road seven or more miles distant with its chapels. Brownsville itself was the only old population center in Cameron and Hidalgo counties reached by the railroad, which became a racial dividing line between the “Mexican” and “Anglo” populations for the very first time in the history of the Valley. The new “Anglo” farmers had mostly negative stereotypes of those of Mexican origin, and had no economic nor social reasons to regularly mingle with those of Mexican descent as the previous very small minority of non-Mexican merchants and ranchers had. This seismic change in population, settlements, and cultural attitudes had a tremendous impact on the Brownsville mission.

Ever since their permanent arrival in 1852, most of the Oblates in the Valley had concentrated their attention on the Spanish-speaking of Mexican origin. This had been due not only to that group’s omnipresence and overwhelming majority which had made their language and much of their culture the shared culture of everyone in the Valley, but perhaps also to the French Oblates’ own cultural preference. Only a few such as Fathers Parisot, Gaudet, and Vandenberghe had sought to emphasize giving equal attention to the small English-speaking minority. Father Martinet had counselled this in 1883, as did the provincial in 1899, Father Lefebvre, who exhorted the Oblates in Brownsville: “Let us see if we cannot do something more for them [the Americans] than in the past and especially let us make every possible effort to learn their language.”

Nevertheless, most of the Oblates had generally remained much more interested in and adept at Spanish in comparison to English.

With the demographic changes introduced by the building of the railroads, more of the Oblates realized that their ministry would also need to expand accordingly. In late 1904 Father C. J. Smith, who had pastored the English-speaking St. Mary’s Church in San Antonio for most of the two decades the Oblates had been there, was transferred to Brownsville to take charge of the “American” congregation. He immediately took a census of the growing “American” element and proposed that a separate church be built for them, as had been the case in San Antonio for half a century already. The other Oblates were cautiously open to the idea, but various complications intervened. Continued population growth finally brought about the building of Sacred Heart Church for the English-speaking in 1912-1913 on the same block as St. Joseph College, with the parish made an independent Oblate residence in early 1914.

In thus removing the English-speaking parishioners from the Immaculate Conception Church, it became for the first time a solely Spanish-speaking one, still serving the entire city and its outlying mission territory. But even this traditional ministry was experiencing major changes: the priests were challenged to strengthen if not redirect their efforts to reaching out to the influx of new Mexican immigrants, unfamiliar to the Oblates and in many cases not married by the church nor closely involved in parish life. House visitations and continued catechetical work were urged by the provincial. The so-called “Mexican problem” was beginning to emerge in the thoughts and language of the Catholic clergy.

One response was, not unpredictably, free parochial schools. The new Second United States Province had immediately sold to a developer the La Lomita property, a major financial fruit of the Brownsville Oblates’ ministry which in previous decades had caused them considerable expenses. The provincial council appropriately decided in early 1907 to dedicate $1,000 a year from the interest of the La Lomita Fund to support a free parochial school in the Brownsville parish. So in 1908 the Guadalupe school for boys owned and operated by the Sisters of the convent since 1889 was changed into a parochial school for girls, and the new school of the Immaculate Conception for Mexican boys was built, staffed the first six months by the Marist Brothers of the college and thereafter by the Sisters. With the continued help from the Lomita Fund, the schools flourished.

At the same time that these changes were taking place within the city of Brownsville, the parish’s mission territory became dramatically reduced. In 1907 it still covered all of Cameron County and included 250 mostly small villages and ranches containing 8,000 inhabitants, as well as Port Isabel. The territory was still divided between only two missionaries, the one visiting below the Arroyo Colorado and the other above it. But within four years the Brownsville mission was reduced to a small corner of what it had been. In 1908 the new Kingsville parish staffed by diocesan priests to the north of Cameron County removed the very large but very sparsely populated La Parra ranch (most of the future Kenedy County) from the Brownsville mission, taking away half of the latter’s territory but little of its actual ministry. But the legacy of Father “Juan de la Costa’s” faithful service to La Parra would bear unsuspected fruit for the Oblates. Gratitude for his dedicated ministry was a principal motive for the later major bequests to the Oblates by the last direct Kenedy heirs. Those bequests, besides being of enormous financial benefit, led to the move of the provincial novitiate from La Lomita to La Parra in 1961 and La Parra’s subsequent transformation into Lebh Shomea House of Prayer, a unique contemplative retreat ministry which is thus but one more outgrowth of the Brownsville mission.

In the lower Valley itself, the advent of the new railroad towns and farms and phenomenal population growth led in quick succession to the establishment of an Oblate missionary residence in 1909 in Mercedes and in 1912 in San Benito. This suddenly shrunk the Brownsville mission territory down to a distance of only about twelve miles, except for Point Isabel, spreading like a hand-held fan from the city. Nevertheless, this still included the downriver chapels of Santa Rosalia and San Rafael ; the upriver chapels of Villanueva, El Carmen, and the new San Pedro (1911); and the new chapel of Puente de los Negros or La Palma (1911) on the railroad line toward San Benito. Together with Point Isabel, that made seven chapels in the now very compact mission territory.

Even if very much reduced in size and now a “national” parish, the Immaculate Conception Church in 1914 served 12,000 Catholic Mexicans in the expanding city itself and another 3,000, including a few non-Mexicans, in its mission territory. A third free school, San Francisco de Asís, begun in 1913 and financed by Mrs. Felicitas Yturria as a coeducational Catholic institution, initially taught by Mexican lay women and then by the Sisters since 1916, was also under the Oblates’ supervision. The priests taught catechism in all three schools. But in 1914 the province ceased its contribution from the Lomita Fund, leaving the parish responsible for supporting the boys’ school. Thus it is not surprising that in 1925 the parochial school for girls was suppressed, and the Immaculate Conception school was made coeducational. This still left two coeducational parochial schools, Immaculate Conception and San Francisco, both full to capacity, with the latter being supported by the deceased Mrs. Yturria’s bequest. The lower grades were taught in Spanish; some of the Sisters teaching in them did not know English. The Oblates took on yet another chaplaincy ministry when the Sisters of Mercy started a hospital in 1922; when a diocesan chaplain was assigned in 1923, the Oblates were asked by the bishop to continue to visit the Mexican patients there, obviously the great majority!

Outside the city, the chapel at Santa Rosalia and the village itself were swept away in 1915 by the flooding river and its altered channel. On the other hand, sometime during these years a chapel was built at Salado (South Point) near San Rafael; it remained in service only a few years. In 1916 the priest assigned to visit the seven chapels and other ranches was also responsible for Masses at the convent, music at the parish, and catechism at the Sisters’ Academy. In order to make it possible for him to say a second Mass at one of the chapels on Sunday (after the convent Mass and directing music at the parish Mass) and occasionally during the week, the Oblate community bought its first automobile, a Ford. Clearly the “ranch” ministry by this time was no longer the traditional ranch ministry, but rather a quick Sunday outing plus special occasions. In that same year the chapel at La Palma ceased to be used. By 1920 the only outlying chapels other than Point Isabel still being visited were Villanueva, San Pedro, and San Rafael. The Ford must have gradually transitioned to city use, since in October 1923 permission was asked to buy a second one. The old one being used in the city was to be given to the priest who visited the chapels. His horse and buggy were both wearing out, and he needed and wanted to visit the countryside not only for the traditional monthly Sunday Mass and rosaries, but also for visiting the sick and teaching catechism (there were no longer women catechists at the ranches). Thus the era of the horseback “Cavalry of Christ” finally came to an end in Brownsville.

Focus on the City: Filial Chapels, Gradual End of the Ranchero Ministry (1924-1964)

During these years there were usually only four Oblate priests and one Brother at the Immaculate Conception house. With the diminution of the outlying chapels and the growth of Brownsville, their ministry was focusing more and more upon the Mexican population in the city itself, with their large parish, three parochial schools, and hospital ministry. They were also responsible for the priestly ministry at the Incarnate Word Sisters’ academy and two convents (the second for the San Francisco school) and the Marist Brothers’ college and community.

For several years the Oblates had been noting the need to build auxiliary chapels, destined to become separate parishes, in the new residential additions developing in the city. Finally in 1922 a sizeable property was bought for the future Our Lady of Guadalupe parish twelve blocks to the northeast of Immaculate Conception Church, at the urging of the new bishop who was concerned about Protestant activity in that neighborhood. While funds were still being collected for the new church, the abandoned chapel of Salado was moved to the property in 1924 to serve as a provisional church. Mass was offered every Sunday and catechism during the week, by none other than the priest in charge of the outlying missions. In 1925 the number of priests at the parish was increased to five, to allow the priest in charge of the Guadalupe chapel to dedicate his efforts entirely to developing that projected parish. With most of the funds for the new church finally on hand in 1927, the church was built and a rectory provided by putting together the temporary chapel and the old chapel of La Palma. Our Lady of Guadalupe was officially declared a separate parish on December 20, 1927; it would remain under Oblate direction until 1971.

During the same years that the Guadalupe church was being built, the Immaculate Conception house in Brownsville provided hospitality to several refugee clergy fleeing persecution in Mexico. One or the other of these priests stayed for longer periods helping the Oblates in ministry in Brownsville, as others spread out to other Oblate parishes along the Rio Grande.

In the years 1927-1930 Port Isabel (the changed name of Point Isabel, as it was developing its port capacities) briefly obtained a resident priest without it being planned. Father Paul Lewis was sent there to restore his health, as had happened with other Oblates in previous decades. Unlike the others, however, he remained, and in April 1929 the provincial council officially made Port Isabel a separate residence. But in June 1930 Father Lewis was transferred to Sacred Heart Parish in Brownsville when its pastor drowned at Port Isabel, and Port Isabel reverted to being a mission visited from Brownsville. During this same time a wood-frame chapel was built at Olmito in the country outside Brownsville by Oblate Brothers sent by the provincial, and repairs were undertaken on the other chapels. A place called Santo Tomás was also among the missions visited.

Close on the heels of the chapel expenses, the Yturria bequest supporting the San Francisco parochial school In Brownsville expired in 1930. The year before, the Oblates had bought property in the town addition of West Brownsville in view of a future parish to be called St. Joseph. But by the end of 1930 the Oblates began noting that the parochial schools were a “big drain on church revenues,” which made it very difficult to pay church debts and to undertake the many repairs and improvements needed on the parish church. The St. Joseph construction plans were canceled, not to be revived until after the Depression and World War II. Tuition was instituted at the San Francisco school, but in 1932 the Sisters asked for it to be suppressed in order to draw more children. Financially the Oblates were at a loss what to do: “The general depression and the complete destitution of the Church finances form the greatest problem for the next y ear.” Nevertheless, they agreed to cancel the tuition at the San Francisco school given the poverty of the families and the fact that the two Sisters received no salary. They also determined to reduce the number of salaried Sisters at the Immaculate Conception school to two if the number of pupils there did not increase.

Dealing another hard blow to the Oblates in Brownsville, a strong hurricane in September 1933 blew out the roof of their residence and knocked down all the wooden-frame chapels, leaving only the more solid one at Villanueva. The chapel at San Pedro was able to be rebuilt fairly easily, since it had collapsed in sections. The lumber from the demolished chapels at Olmito and Santo Tomás was destined to help resurrect once again the chapel at Port Isabel. When Father Charles Buckley was assigned to Brownsville in 1938, he was placed in charge of Port Isabel. The bishop immediately began arranging to make that place a separate parish pastored by Father Buckley, with responsibility also for Los Fresnos, formerly part of the San Benito territory. Thus Port Isabel finally ceased to be part of the Brownsville mission territory. That left only two chapels, Villanueva and San Pedro, outside the city to be visited from the Immaculate Conception Church. San Rafael at South Point no longer had a chapel, so the public schools there were used for Sunday services. Chapel-less Olmito was also still visited. And there still remained many other ranches.

In Brownsville itself, the priests taught catechism in all the Catholic schools, as well as in the church for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd communion children. Additionally, young men of the A.C.J.M. sodality taught every Sunday in eleven centers spread throughout the parish. Besides the young men’s society, there were also at this time the longstanding societies of the Holy Rosary, Children of Mary, and Altar Society, as well as the Holy Name Society and the Knights of Columbus. At the conclusion of World War II, the Oblates at Immaculate Conception were finally able to turn their attention again to developing other Mass centers within their section of the city. In 1945 a former Protestant church was acquired for use in the Santo Tomás neighborhood. And in 1949 the St. Joseph property, bought twenty years earlier in the northwest part of town, finally received an old army chapel moved from Fort Brown. Both of these filial chapels were treated as quasi parishes in regard to pastoral care, with a priest assigned primarily to each of them.

Within a few years, in 1953, St. Joseph was made an independent national parish staffed by Oblates for the Spanish-speaking. This reduced the territory of the Immaculate Conception Church to the old pre-railroad city, except for a narrow section to the north, cutting off all the growth that had occurred to the northwest since that time. This also removed the care of the upriver missions from Immaculate Conception Church, assigning them rather to one of the other parishes. For the first time in a century, the Oblates at Immaculate Conception house no longer had missions to visit outside the city: for them the ranchero era had ended. St. Joseph Parish continued to be served by the Oblates until 1998. Santo Tomás, on the other hand, has remained a filial chapel of Immaculate Conception Parish to the present day. It was judged to be too close to dismember the parish, which would have been left with very little territory outside the old business district.

In 1952 a new parochial school was completed, replacing the old Immaculate Conception School and probably also the San Francisco School, which had certainly fulfilled the hopes of its foundress and benefactress for four decades. The Oblates’ attention was then directed toward the poor “Los Tomates” neighborhood nearby to the east, above Fort Brown. In 1955 they bought some property there that already had a house and a former Protestant church that could serve as a catechetical center and site for a future filial church. At the provincial’s suggestion, a few months later the parish obtained some catechist Sisters, the Madres Misioneras de Jesús, María y José, to help reach the many children in the parish who were not in Catholic schools nor attending communion classes. The Sisters were housed on the newly acquired property, and in 1961 the filial chapel of the Holy Family was built. By this time the Cursillo renewal movement had arrived in Brownsville, and the poor Muralla barrio by the river had become one of the catechetical centers of the parish. In 1966 Holy Family church became the third filial chapel of Immaculate Conception Parish within the city, and the sixth in all (Mercedes, San Benito, Our Lady of Guadalupe, Port Isabel, St. Joseph, Holy Family) to become a separate parish, all staffed by Oblates. The Oblates continued to serve at Holy Family Parish until 1996.

At Immaculate Conception church itself, the growth of the Mexican American generation in the parish was clearly indicated by 1956 when Father Santos, the Spanish Oblate pastor, asked for a young “American” assistant because he intended to start at least one Mass in English for the youth. Upon the centennial of the dedication of the church in 1959, a life-sized statue of St. Eugene was placed by the city in the park facing the international bridge to Mexico. It remains there to the present, symbolizing the Founder’s great desire that the Brownsville foundation serve as a gateway to missionary work in Mexico. At the church itself, during these years there were eight crowded Masses each Sunday with an average total attendance of 3,500.

Cathedral of New Diocese, Church of the Poor (1965 – present)

In 1965 the Diocese of Brownsville was created, and the historic Immaculate Conception church was designated the cathedral. Father Emanuel Ballard, one of the Oblate priests at the cathedral, was named chancellor of the new diocese, and other Oblates were appointed heads of other chancery departments. Ironically, or perhaps appropriately, the church’s new status as cathedral was paralleled by the growing impoverishment of its neighborhood. The city was expanding rapidly, new commercial centers were being established, and the old commercial center next to the international bridge to Mexico waned accordingly. Although many older members of the former town elite continued to remain attached to the church, the more typical person coming to its offices was the transient from the bus station across the street, the immigrant from Mexico just a few blocks away, or the homeless. As the neighborhood declined, the number of Masses was gradually cut back, and the priests on staff were reduced to three or even two.

Another sign of the times was that when Holy Family Parish was established in 1966, it was no longer named a national parish for the Spanish-speaking, as Immaculate Conception and Our Lady of Guadalupe and St. Joseph had been. In fact, all these parishes actually became territorial parishes for all those within their boundaries. Since Sacred Heart parish was experiencing its own major decline as most of the business elite moved to newer sections of the city, its former function as the official parish for the English-speaking throughout the city ceased and it was made a filial chapel within the parish territory of Immaculate Conception in 1967. Its small but committed and tenacious congregation was unable to prevent the church building from gradual deteriorating, but in 1979 a restoration campaign began with widespread and even ecumenical community support. The filial church of the Sacred Heart continues to have one Mass on Sundays. Santo Tomás remains the other filial chapel of the cathedral to the present day.

Oblates at the Immaculate Conception Cathedral have continued to play significant roles in the life of the Brownsville community to the present day. In 1967 Father Ballard built the Newman Center at the public college campus just a few blocks away, and in recent years Father Armand Mathew has served as a civic engagement coordinator at the university, while also promoting a campaign to increase voting awareness among the youth of the city. Various Oblates gave strong support to Valley Interfaith, a faith-based community organizing project to strengthen the people’s voice in bringing about social and educational improvements. During the pastorate of Father Warren Brown in the late 1980s, the Oblates at the cathedral were strongly involved in ministry to the undocumented refugees from Central America. It was also at that time that the parochial school was closed, due to the inability to continue to financially sustain it.

During more than a century and a half of Oblate presence, the Missionary Oblates at Immaculate Conception Church have continued to be true missionaries among the poor. During the nineteenth century Oblates from this community founded the Roma, Eagle Pass, and La Lomita missions all along the Mexican border in Texas, and the Matamoros, Victoria, and Agualeguas missions in Mexico. During the twentieth century they helped to found the brief re-entry into Mexico in 1902-1914, the parishes of the Rio Grande Valley towns of Mercedes, San Benito, and Port Isabel, and the Brownsville parishes of Our Lady of Guadalupe, St. Joseph, and Holy Family. Today the historic Immaculate Conception Cathedral, “mother of missions,” is the only parish still staffed by Oblates in Brownsville other than the recent foundation of San Eugenio Church. This last parish, one of the first in the world to have our Founder as patron, was begun at the bishop’s invitation in 1996, a few months after Bishop de Mazenod’s canonization, in a poor neighborhood of recent immigrants in Brownsville.

Robert E. Wright, o.m.i.