- The Oblate Personnel

- Relations with the Bishops and the Clergy

- The Seminarians

- Important Events; Expulsion

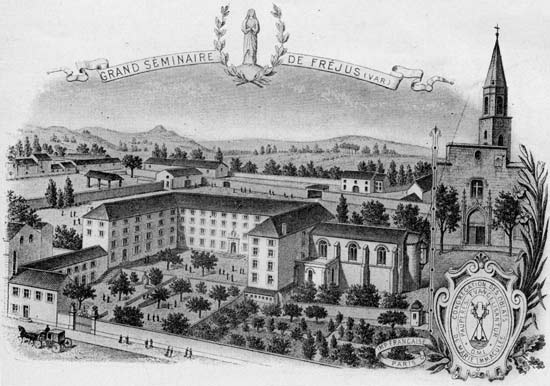

The Founding

In July of 1851, Bishop Casimir A. J. Wicart, bishop of Fréjus from 1845 to 1854, handed over the administration of his major seminary to the Oblate Congregation. Founded in 1677, this seminary had been closed during the Revolution when the diocese was suppressed. When the diocese was re-established in 1823, the seminary reopened under the title of the Immaculate Conception in its former building erected in 1776. It was at that time that Bishop Charles Alexandre de Richery, bishop from 1823 to 1829, appointed Father Emmanuel Maunier as superior of this institution. Already since 1816, Father Maunier was a member of the Missionaries of Provence. In view of his appointment as head of his seminary, Bishop de Richery dispensed Father Maunier from his vows.

From the time of his arrival in Fréjus, Bishop Wicart knew Bishop de Mazenod. In the spring of 1846, Bishop Eugene de Mazenod received him at the bishop’s house as a visitor for a few days. Bishop Wicart met Bishop de Mazenod anew on the occasion of the provincial council of Aix in 1850 and, in the same year, in the cathedral of Marseilles, acted as the co-consecrator of Bishop Jean Francis Allard. We do not know why he made this decision, a decision which was not taken without reflection, since Father Ortolan writes: [Bishop Wicart] “took advantage of the fact of his geographic proximity to plead eloquently the cause of his major seminary which he wanted to entrust once again to the Oblates. Since his repeated letters had not produced the results he so ardently wished, he made the trip to Marseilles to deal with this affair in person and, to resolve this matter as expeditiously as possible.” We do know that there was a shortage of clergy in the diocese of Fréjus and, it seems, bad morale among the seminarians. Upon their arrival in 1851-1852, the Oblates sent home six students and four more students the following year.

Bishop de Mazenod joyously ‑ and it seems without consulting his council ‑ accepted this new foundation, all the more so because in the General Chapter of 1850 a few articles on the direction of seminaries were added to the Rule. Already in the month of July, he communicated this news to Father Casimir Aubert in England and to Father Henry Tempier who was making a canonical visit to Canada, to Father Étienne Semeria in Ceylon and to Father Pascal Ricard in Oregon. It was he, himself, who, on August 15, 1851, signed along with Bishop Wicart the “agreement” by which the bishop of Fréjus handed over the direction of his seminary to the Oblates in perpetuity. The Oblates would be responsible only to the bishop. They would be fed and lodged and would receive a salary or 1200 francs for the superior and 700 francs for each of the directors. On its part, the Congregation committed itself to supply at least five priests to teach and give spiritual direction as well as taking on responsibility for the financial administration, admissions and the expelling of seminarians, etc.

The Oblate Personnel

There were six priests who were superiors of the house: Jean Joseph Lagier from 1851 to 1856, Jean Joseph Magnan from 1856 to 1859, Mathieu Victor Balaïn from 1859 until his appointment as bishop in 1877, Toussaint Rambert from 1877 until his death in 1889 Jean Corne from 1889 until his death in 1893 and Eugène Baffie from 1894 until the expulsions of 1901.

Over the span of fifty years, thirty-five priests functioned as professors and directors. Just like in all Oblate houses of the time, their stay, on the average, lasted only three years each and for some even less. But Father James Bonnet remained for 30 years at his post; Father Élie Nemoz remained 27 years; and Father Étienne E. Chevalier remained 20 years.

According to the reports of the superiors and the canonical visitors, the directors showed themselves equal to the demands of their important task. In an 1853-1854 report, Father Lagier wrote: “As for their part, our priests contributed significantly to the betterment of the situation. Each one collaborated as best he could through his enthusiasm, his regular observance of the house rules and his positive spirit. Daily adoration of the Blessed Sacrament and of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the sacred heart of Mary, the holy office chanted in common, meditation themes trad aloud three or four times a week by each of the directors in turn, spiritual reading with a few explanations, etc., must have also powerfully contributed to the happy results which I have mentioned.”

After his canonical visit in 1855, Father Casimir Aubert, the provincial of Midi, added: “As a result of the personal interviews that I held with the priests of Fréjus, I have become convinced that they have a perfect understanding of their position and that they are equal to the demands of their vocation, either as religious, or as seminary directors. Their good morale, their unity, their prayer life, their regular observance is a source of edification for the seminarians…” The same observation is made by Father Jean Joseph Magnan in 1857-1858: “As for the situation, it continues to be good and satisfactory under every aspect. Our priests go about their business. Each one of them diligently discharges his duty and strives, according to his means, to make the students progress in the area of church knowledge they are assigned to teach. In their role as directors, they apply themselves to helping the superior in the very difficult work of forming the seminarians in their prayer life and the ecclesiastical virtues…”

We still have a few letters of congratulations and encouragement the Founder wrote to the directors. In a July 9, 1852 letter to Father Jean-Baptiste Berne, he wrote: “…the docility of your pupils must be attributed more to your example than to your classes.” (Oblate Writings I, vol. 11, no. 1108, p. 89; also, ibidem, p. 101) In a January 31, 1854 letter to Father Adolphe Tortel, he wrote: “Thank God you are not a source of worry at Fréjus.” (Oblate Writings I, vol. 11, no. 1108, p. 182) To Father Berne on February 5, 1854, he wrote: “The diocese will feel the benefit of your good teaching and of your edifying example, and God will bless you for the good that you have done for souls.” (Oblate Writings I, vol. 11, no. 1108, p. 183-184), etc. From the very first years they arrived at Fréjus, Bishop de Mazenod required that the directors should spend their vacation time in an Oblate community and should only leave to preach a few retreats. Subsequently, that is what they did. For example, we know that from 1873 to 1879, they preached 18 retreats during their vacation time and 25 from 1886 to 1892.

In the report of his canonical visit in May of 1859, Father Casimir Aubert wrote once again: “The situation is satisfactory either in what has to do with the priests themselves or what has to do with the seminarians. In general, the priests are seriously involved in their work and care for their students as they should both in regard to their studies as in regard to their prayer life. Unity and good relations reign among them, as well as fidelity to their duty with regard to the rule and the deference they owe the superior. As for the students, their attitude is good; they seem to be happy with their directors; they observe the rule rather well. Morale among them is good and they give ongoing evidence of a genuine prayer life…”

In his report to the General Chapter of 1873, the provincial of Midi mentioned each of the houses of the province and, at the end, stated: “There remain our two large seminaries of Ajaccio and of Fréjus. There is no point here in stressing the importance of these works and the honour they bring to the Congregation. Those of our priests assigned to these works fully understand everything such a task demands in regard to dedication, prayer life, solid virtue, discretion, discernment and diligence in the work. They understand it and they strive to carry it out. Moreover, all of them love their work, in spite of its harsh and wearying aspects. It is only just to grant them this acknowledgment. I especially love to point out here that the two superiors of Ajaccio and Fréjus have won the highest degree of confidence of the episcopal administrations that they serve.” (Missions, 11 (1873), p. 292)

There is only once, and that in 1888, in the correspondence and the reports that one finds an observation made by Bishop F. H. Oury who expressed dissatisfaction with the directors because they did not take recreation with the students. On the other hand, in an August 19, 1901 pastoral letter which announced the expulsion of the Oblates, Bishop J. E. Arnaud wrote: “When they step out of the Fréjus seminary door, a seminary which has housed them for fifty years, those who were in charge take with them our sorrow at seeing them leave, a sorrow, alas, which is presently exacerbated because they do not know where they will go in the future. They take with them the esteem of our eminent predecessors who, in the four episcopates preceding our own, maintained for them an unfailing confidence which gives witness of the honour in which they were held. They also take with them the esteem of their students who will remember the benefits they received from their clerical formation which rendered them worthy of the important ministry which was confided to them…” (Missions, 45 (1907), p. 427-428)

Relations with the Bishops and the Clergy

It is not an easy thing for a religious congregation to gain acceptance when it replaces the diocesan clergy in staffing a seminary. It seems that, at Fréjus, the transfer happened smoothly in 1851. That is what we see in the letters of the Founder and in several reports. In 1853-1854, Father Lagier wrote: “The warm welcome which prevailed at our beginnings has not for a moment failed us since then. We can even say that the esteem and the affection which the worthy bishop who called us here has unceasingly lavished upon us as well as the excellent chapter and the whole body of the worthy clergy of Fréjus has only grown with time.” The same observations were made by Father Casimir Aubert in 1858: “As for the relations which exist between our priests and the lord Bishop, they began under the most favourable auspices and have maintained themselves in the best of terms.” “Relations with the clergy and especially with the diocesan authority are equally satisfactory.”

At the General Chapter of 1856, the provincial praised the first superior, Father Lagier, who “introduced traditions of prayer life, regular observance and work which filled the bishop with joy,” but that same year, Bishop de Mazenod wrote to Bishop Jordany, bishop of Fréjus from 1855 to 1876 that he was recalling the superior because of “some slight shadows which have fallen on our worthy Father Lagier who, it seems, made the mistake of expressing himself too openly about the opportunity of admitting into your council those kind of people who are, however, highly recommended.” As a result, there arose some antipathies which made it difficult for him to continue in his position.

Father Magnan, appointed superior in 1856, was never liked by Bishop Jordany. He had to be replaced in 1859. In the September 26, 1858 report of the General Council, we read this about him: Father Magnan will receive “a few bits of rather guarded advice about the negligence in carrying out his duties of superior for which he is being blamed.”

Father Balaïn, the superior from 1859 to 1877 was held in esteem by Bishop Jordany. They cooperated in building a beautiful chapel at the seminary. Some misunderstandings did, however, arise in 1871 and especially in 1874. At the time, Bishop Jeancard wrote that, influenced by the people in his immediate circle, “Bishop Jordany complained about him. The complaints were groundless, but made it henceforth impossible to enjoy the relation of mutual trust that should always exist between the bishop and the superior of his seminary, a member of his council.” Among other things, the bishop accused him of setting “too much store by the youth and perhaps sometimes showing a bit of bias.” At the June 17, 1874 council, the conclusion was reached that “this could be grounds for a warning and not for a change of job.” Everything soon settled itself. Bishop Jordany resigned in 1876 and Bishop Balaïn was appointed bishop of Nice in 1877.

An 1882 letter from Father Chevalier tells us that there were some strained relations between Father Rambert and Bishop J. S. Terris, bishop from 1876 to 1885. Bishop Terris wanted to entrust “the main direction” of the seminary to two canons in conformity with the directions of the Council of Trent. Bishop Wicart, had, however, exempted the Oblates from this requirement. As a result, Father Louis Soullier made a canonical visit and resolved to ask for an indult from Rome.

Upon his arrival at Fréjus, Bishop F. H. Oury, bishop from 1886 to 1890 had already been prejudiced against the superior by members of his immediate circle. They found fault with the superior in not allowing the students to choose their own spiritual directors, of having furnished the chapel in sumptuous fashion, of not having approved of some decisions taken by the bishop’s committee, etc. The General Council were on the point of deciding to replace Father Rambert when they learned of his death on July 12, 1889.

Father Corne, the superior from 1889 to 1893, was always held in high esteem by the seminarians and in good relations with the bishops: Bishop Oury, then Bishop E. I. Mignot, appointed in 1890.

Father Baffie was superior at the time of the expulsions in 1901. His relations with bishops Mignot and Arnaud, from 1900 on were good. In 1893, the Oblates were even offered the direction of a minor seminary which the authorities wanted to open at Fréjus to complement the minor seminary of Brignoles.

The Seminarians

Upon the arrival of the Oblates in 1851, the seminary housed a student body of about 100 students. In his report to the General Chapter of 1879, the provincial of Midi stated that, in six years, 86 new seminarians were received and there were 72 ordinations. In 1893, there were still 60 students in spite of a palpable drop in vocations.

It seems that satisfaction was always expressed concerning the teaching of the professors, but the professors sometimes complained about the students’ lack of interest in studies. In his act of visitation, in 1855, Father Aubert wrote: “The major seminary of Fréjus is doing very well, both as regards studies as well as for prayer life. In the brief time from when our priests took charge, a noticeable improvement has taken place in every regard.” In 1858, Father Magnan made the following observation: “Enthusiasm for study leaves something to be desired and some measures will have to be taken to help our seminarians understand their obligation in this regard and to bring them to more diligence and, as a result, a greater degree of knowledge of the ecclesiastical sciences.” In the course of his canonical visit in 1866, Father Augier noticed that studies were weak. He attributed that to “a weakness in the area of classical studies being taught in both the minor seminaries.”(Brignoles and Grasse)

Assessments of spiritual formation and the ecclesiastical spirit were more laudatory. In 1853-1854 in his report, Father Lagier wrote: “The movement toward betterment and for prayer life is strongly developed. The spirit of unity, of regular observance and peace manifested itself brilliantly.” In 1857-1858, Father Magnan shared the same reflections: “On their part, these young people respond faithfully enough to the care given them in the seminary… Overall there is meticulous observance on their part in following the rule of the house, and diligence in the practice of Christian and priestly piety. A certain number are more advanced and show that they are inspired by a genuine fervour.”

In 1888, there was a decline when they were accusing Father Rambert of being too harsh and of not approving certain appointments made by the bishop. In the June 5, 1888 report of the General Council, we read: “The students are revolting against authority. An insulting placard was posted to the door of the superior’s room. It stated that the superior should leave and all the Oblates with him. It is impossible to deal severely with this; it is impossible to communicate the facts to the bishop. He would answer: “Your students are treating you like you treat them” because he is convinced the priests are against him.”

Almost every year, the annual retreat was preached by an Oblate. Others preached, as well. the parish retreat (for example, Father Ambroise Vincens in 1856, Father Marc-Antoine Sardou in 1862) or the Lenten series at the cathedral (for example, in 1868, 1886 and 1898) as well as missions in the diocese (for example, in 1891 at Belgentier, in 1898 at Fréjus, etc.). About fifteen seminarians or young people from the diocese subsequently joined the Congregation.

Important Events; Expulsion

Father Joseph Fabre, the superior general, made several visits to Fréjus. We know of those of 1863, 1869 and 1886. On January 25, 1866, at the seminary, they celebrated in solemn fashion the fiftieth anniversary of the foundation of the Congregation with Bishop Jordany and Bishop Jeancard in attendance. During the 1870 war, the seminarians were sent home and the seminary was occupied by the army. In 1876, with great pomp and circumstance, they greeted the new bishop, bishop Terris, a friend and fellow-student of Father Charles Baret and one well known to the Oblates of Notre-Dame de Lumières.

During the expulsions of 1880, the French government was especially aiming at taking education away from the religious men and women. In an October 4, 1880 letter, the minister of public worship asked Bishop Terris to hand over the seminary to the diocesan clergy. On October 20 of that same month, the prefect of the Var signed a “decree of dissolution” of the Oblate community at the seminary. On October 30, the priests of the community answered that they were members of the diocesan clergy in virtue of an indult of secularization by the Pope. On December 1, the prefect informed Father Rambert that the application of the decree of dissolution was suspended and that the directors could continue their work.

The government decisions of 1901-1903 were much more serious. We know that on November 14, 1899 Waldeck-Rousseau, the prime minister and the minister of public worship had tabled a legal program of action with regard to associations and religious congregations. The law was passed on July 1, 1901: Congregations established without government approval were declared unlawful if they did not without delay ask for this authorization, an authorization which was refused in 1903. In Fréjus, events had moved apace. Waldeck-Rousseau wrote to the bishop on March 14, 1901. He told him that religious were still directing the seminary and insisted that this abuse must come to an end, otherwise the government would see itself “obliged to reclaim the government building which had been allocated to serve as the major seminary.” The bishop at the time was Bishop Arnaud. The bishop responded on March 29. He stated that the seminary was being run by three ex-Oblates who had been secularized in 1880 and three other young religious. He added: “In order to accommodate the government’s views, in order to avoid getting myself into an impossible predicament and in order to avoid stirring up recriminations in my diocese by making changes that are too radical and too abrupt, I beg your kind indulgence, honourable minister, to authorize me to keep in my seminary only two of the three former directors incardinated and secularized since 1880. The assistance of these two gentlemen, grown old in their twenty-five years of teaching in this establishment, who have, besides, a record of irreproachable conduct with regard to the civil authority as well as the church authorities and are considered as belonging to my clergy because of their uninterrupted and constant residence for a quarter of a century, they afford me an indispensable element for a smooth transition to a new regime. I reserve the right to add to them, when the academic year begins, as many priests as the extreme scarcity of my subjects will allow, a condition which will put me in the difficult situation of leaving about twenty posts without anyone to fill them…”

That is what took place. It was approved by the government and announced officially in a long pastoral letter signed August 19, 1901. The direction of the seminary was entrusted to the diocesan clergy. Fathers Bonnet and Nemoz continued their teaching until 1906. Compelled to do so by government decree, the other Oblates left the seminary. The bishop stated unequivocally in his pastoral letter. “What a pleasant thing it would be to profit once again from the experience of those prayerful and learned religious to whom our venerated predecessor had entrusted the direction of the seminary of Fréjus. Circumstances, compelling and as much beyond our control as it was beyond theirs did not allow them to continue to offer us their much appreciated help. Even though we have only been able to enjoy that help for the short time in our clerical family that, in these last two years, has been ours, at least we have for many long years seen them at work with the devotion of distinguished masters in our diocese of origin of Marseilles, having had the benefit of being taught by the sons of Bishop de Mazenod who consecrated us bishop and who, with a kindness the memory of which will not leave me until the day of my death, as a young priest, graciously accepted to associate me with his noble person in ministry in his cathedral parish…” (Missions, 45 (11907), p. 419, 427-428)

Yvon Beaudoin, o.m.i.