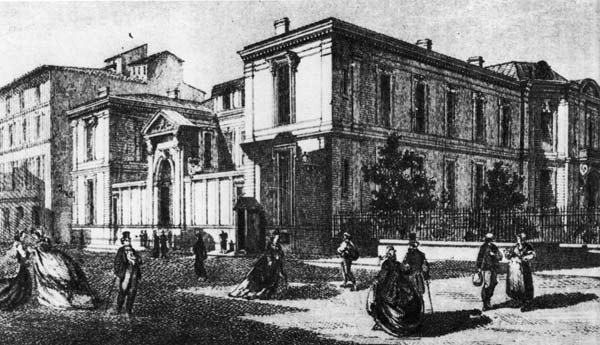

The bishop’s house or episcopal palace of Marseilles, situated near the cathedral, was built during the last half of the 17th century. During the Revolution, it served as a storehouse for military articles and equipment. When the diocese was reestablished in 1823, the restoration of the bishop’s palace cost 66,000 francs and the work was not finished until the end of 1825. They were, however, badly done and incomplete. Subsequently, the Mazenods and Father Tempier never ceased writing to the prefect of Bouches-du-Rhône and to the minister of Public Worship to ask for new repairs and pieces of furniture. In 1827, the roof leaked; a fire reduced a part of the roof to cinders in 1838. The wind and the sea air was destroying the outside surface of the walls, the doors and the windows. On November 25, 1841, Bishop Eugene de Mazenod wrote the Keeper of the Seals: “The outer side of the facade is a mess, so sorry is the appearance its deterioration presents. On the other hand, if the outer aspect of the bishop’s house suggests a residence that is inhabited, one could hardly believe it was the case once one has set foot in the front door. A shambles is what meets the eye.”

Finally, in 1856, the minister of Public Worship sent to Aix the architects Vaudoyer and Viollet-le-Duc who submitted a plan of restoration to the bishop. On October 22, the bishop wrote: “This will be very appropriate for the person who will be able to benefit from it. At my age, one can only apply oneself to such things for the benefit of one’s successor.” In May of 1858, the estimate of one half million francs for the restoration and expansion of the bishop’s palace was approved by the ministry. The work was carried out in 1859 and 1860. “When he attempted to enter the new building by means of a board propped on a window sill, the board tipped and Bishop de Mazenod suffered a fall of more than a meter.” (Rey, II, p. 832) It was perhaps this fall which was at the origin of his illness and death.

Abbé Timon-David who often went to visit Bishop de Mazenod at the bishop’s house wrote: “He had abandoned the fine apartments on the first floor and was living on the ground floor where everything was extremely denuded, to the point of being well below the standards, not of our rich aristocratic salons, but of the most simple bourgeois residence. I never saw that the furniture or the wallpaper was renewed. A narrow little parlour served as a waiting room. On the left was his office, a very large room, but simple in the extreme. Again on the left, there was a parlour, low-ceilinged, badly papered with old red velvet furniture from Utrecht and, on the walls, oil portraits of the Oblate bishops, amateur paintings if there ever were any. Next was the dining room, more simple still. It was not the sumptuous palace of today. But, the most humble apartment of all was his bed room on the right of the waiting room. It was papered in old blue paper. The bed was without a mattress. He slept on a straw mat and it was only with great difficulty that they were able to convince him to accept a mattress during his final illness. Toward the end, he went up to the first floor when they began the construction work on the bishop’s palace. That is where he died…”

Since the separation of Church and State at the beginning of the 20th century, this palace has been taken over by the police. The bishop lives in a house built by the Oblates on the promontory of Notre-Dame de la Garde.

Yvon Beaudoin, o.m.i.