Meditations to prepare for the anniversary of the first vows of November 1, 1818

As an introduction to this meditation, we reflect on the joy of the Founder and Tempier in their living poverty:

In 1831, commenting on the anniversary of the first day of living in community, he said: “The table which adorned our refectory was one board next to another, set on two old barrels. We have never had the joy of being so poor since we made a vow to be so …”[1]

During the Rognac Mission in 1819, the missionaries had to find their own straw mattresses. Father Tempier wrote: “I do not believe that Blessed Liguori would have found anything superfluous either in our furniture or in our ordinary resources […] and we are so happy with our way of life […] to walk in the footsteps of the saints and to be missionaries once and for all.”

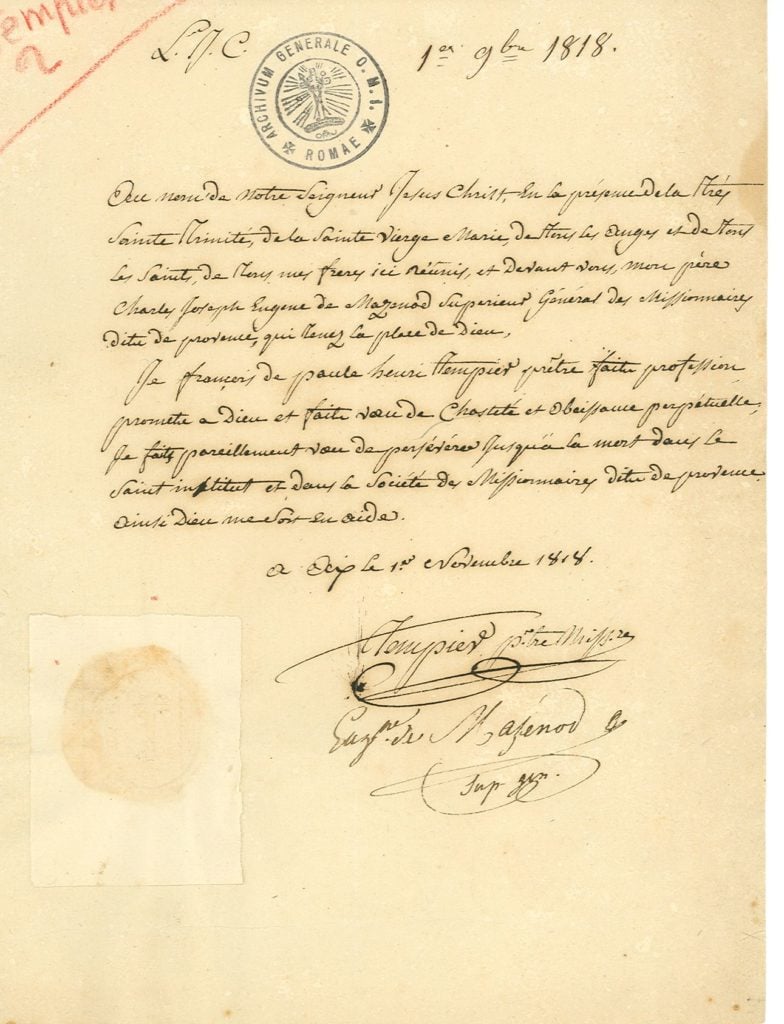

formula of Vows of Fr. Tempier (1818)

This evangelical ideal would soon be inscribed in the Rule of the Missionaries of Provence. First as a virtue – the rule of 1818 speaks of the spirit of poverty, based on summary of a chapter of the book Practice of Christian Perfection by Rodriguez,[2] an author that the Founder had assimilated in Saint-Sulpice. The Rule says: “for the moment, reasons of circumstance have diverted us from this thought (voluntary poverty). We leave it to the General Chapters, which will follow, to perfect this point of our Rule. In the meantime, we will try, without being bound further vow, to understand more fully the spirit of this precious virtue.” And the paragraph ends with these words, “Until these Rules can be enforced, in the strict sense, we will exert ourselves to make them familiar in practice. Superiors will test their subjects in this, not by letting them lack what is necessary, but by providing them with the opportunity to feel some privation, and to realize that the poor cannot always be comfortable and have everything they want.”[3]

We know, through the Founder’s writings, that he wanted to add the vow of poverty: “I wondered why to the vows of chastity and obedience that I made previously, I would not add that of poverty…”[4]

At the end of the retreat, in early November 1820, Father Tempier made a vow of poverty, on condition that the Founder would approve it. “I do not know if you will approve of me, my dear Father. I made a vow of poverty at our renewal; I did so on the condition that you ratify it. The good Lord gave me the grace to appreciate this virtue during our retreat, so much so that I would have done myself a real violence not to have made the vow. […] without even having made the vow, they all want to dispossess themselves of what they have and put everything in common.”[5]

The Founder did not immediately approve of this initiative, but it influenced the Chapter of 1821 which imposed the vow of poverty in the Congregation: “The Very Reverend Father General gave various explanations concerning the practice of the vow of poverty… [the] Founder, decided on it, at once, and placed, in the Rules, that the vow of poverty would be obligatory in the society.”[6]

Photo of Fr. Tempier probably taken in 1865.

Father Beaudouin says that Father Tempier’s poverty caught on among the novices and scholastics and almost caused a shock when he arrived in Marseille as Vicar General in 1823.[7]

To this vow of poverty, we add the spirit of humility and self-sacrifice of Father Tempier. He lived these throughout his life, but in, a very special way, when the successor of our Founder as Bishop of Marseille, Monsignor Cruice, did not recognize the Founder’s will. At first, for the sake of conciliation, Fathers Tempier and Fabre signed an initial agreement. But the bishop went so far as to threaten to obtain the dissolution of the Congregation. Father Tempier made a discreet trip to Rome. After the Chapter of 1862, the bishop threatened to close the Oblate houses in France if a new agreement was not signed, stipulating that three Oblate properties should revert to the bishopric of Marseille. For the sake of appeasement, Father Fabre decided to move the scholasticate from Montolivet to Autun and sell it to the diocese.

Father Fabre would write, in the obituary of Father Tempier, “To leave the native soil, the beautiful sky of Provence and to abandon the tomb where the most beloved of the Fathers rested – and this, at a time when the changes were so painful and new acclimatization so difficult, was not the move away from Montolivet an exile, with its privations, its pains? Yes, and Father Tempier accepted everything. God wrestled with this selfless, Jacob-like man, and the self-sacrificing man emerged victorious from the maw. Montolivet was bought, in time, by the diocesan administration of Marseilles. Who was the man who went to complete the formalities, personally surrender the mother house, sign the deed of sale and hand over the keys? Father Tempier.”[8]

————————————-

Hearing Father Fabre describe this particular moment in Father Tempier’s life, we can question our own availability for the Lord’s mission.

In this year of the 200th anniversary of the vow of poverty, we suggest that we take the opportunity, on the level of the whole Congregation, to reflect on this vow.

In the meantime, we suggest that you reflect on our community witness, in light of this extract from Father Jetté’s commentary on our Constitution 21:, “The Spirit who animates us is the One who guided the first Christians. He invites us to share everything, to pool everything together. Our life will be simple. We even consider it “essential”, for our Institute, “to give a collective witness to evangelical detachment.”[9]

[1] Lettre du Fondateur à la communauté de Billens, le 24 janvier 1831

[2] Histoire de nos Règles par Consentino, T1, p186-189

[3] Règle de 1818, Bibliothèque Oblate texte 1, Ottawa 1943

[4] Les écrits spirituels indiquent la retraite de mai 1818 et le Père Cosentino ajoute que nous ne savons pas la date à laquelle le Fondateur a prononcé ce vœu. Cf. DVO ‘la pauvreté’, note N° 36, p 699

[5] Lettre du P. Tempier au Fondateur du 23 novembre 1820, collection Ecrits oblats II,2 Rome 1987. p234

[6] Cf. Les Chapitres généraux au temps du Fondateur I, par J. Pielorz, Etudes Oblates 1968, p27 deuxième Chapitre général, octobre 1821 à Aix-en-Provence.

[7] Collection Ecrits oblats II,1 Rome 1987. P209

[8] Notices nécrologiques II, du P. Tempier pp24-25

[9] Cf. O.M.I. Homme Apostolique, Rome 1992, p157